Making Rioja Wine

last update: 15 September 2021

The visit to the winery

Included in the our stay at the Hotel Marqués de Riscal was a complimentary visit to the winery. It was probably more superficial than the tourist visits that could be booked separately, but all the visits appeared to focus on the traditional winemaking process and not modern-day industrial processes.

According to the history books the foundations of the oldest still active winery in Rioja were laid in 1825, when the first vines were planted on the Castillo Ygay estate, and a winery (bodega) was started in 1852 by Luciano Francisco Ramón de Murrieta, later Marqués de Murrieta. In 1878 he acquired the estate and vineyards that have become home to one of the great bodegas of Spain ever since. The winery remained in the family until it was bought by Vicente D. Cebrián-Sagarriga, Count of Creixell, in 1983.

In 1858, Camilo Hurtado de Amézaga, Marqués de Riscal, founded the winery that still bears his title. He had been living in Bordeaux since 1836, so he decided to experiment with French varieties at his estate at Elciego and organised his winery following the French model, being the first in the country to use barriques (oak barrels). His wines soon started winning prizes, being favourites of King Alfonso XII (1857-1885), and became so popular that he had to invent the gold wire-netting for his bottles, in a bid to counteract fakes. This device itself became fashionable, as was then adopted as a badge of honour by other top Rioja wines.

Many other wineries were also started around this time. For example, La Rioja Alta was founded in 1890 by five wine growers from Rioja and the Basque country, and is still owned by the same five families today. López de Heredia was founded in 1877 and the Tondonia vineyard was planted on 100 hectares on the left bank of the Ebro River in 1914. They also built a winery in the Barrio de la Estación (the neighbourhood of the railway station) in Haro, next door to La Rioja Alta and other well-known names like Bodegas Bilbaínas (1901) and CVNE (1879). The railway played such a crucial part in the success of the wines that it made sense at the time to establish wineries as close to the station as possible.

Other survivors from this era include Bodegas Montecillo (1872), Berberana (1877), Bodegas Age (1881), Martínez Lacuesta (1885), Bodegas Franco Españolas and Bodegas Riojanas (1890), Bodegas Palacio (1894), and Paternina (1896).

Rioja - a region and a wine

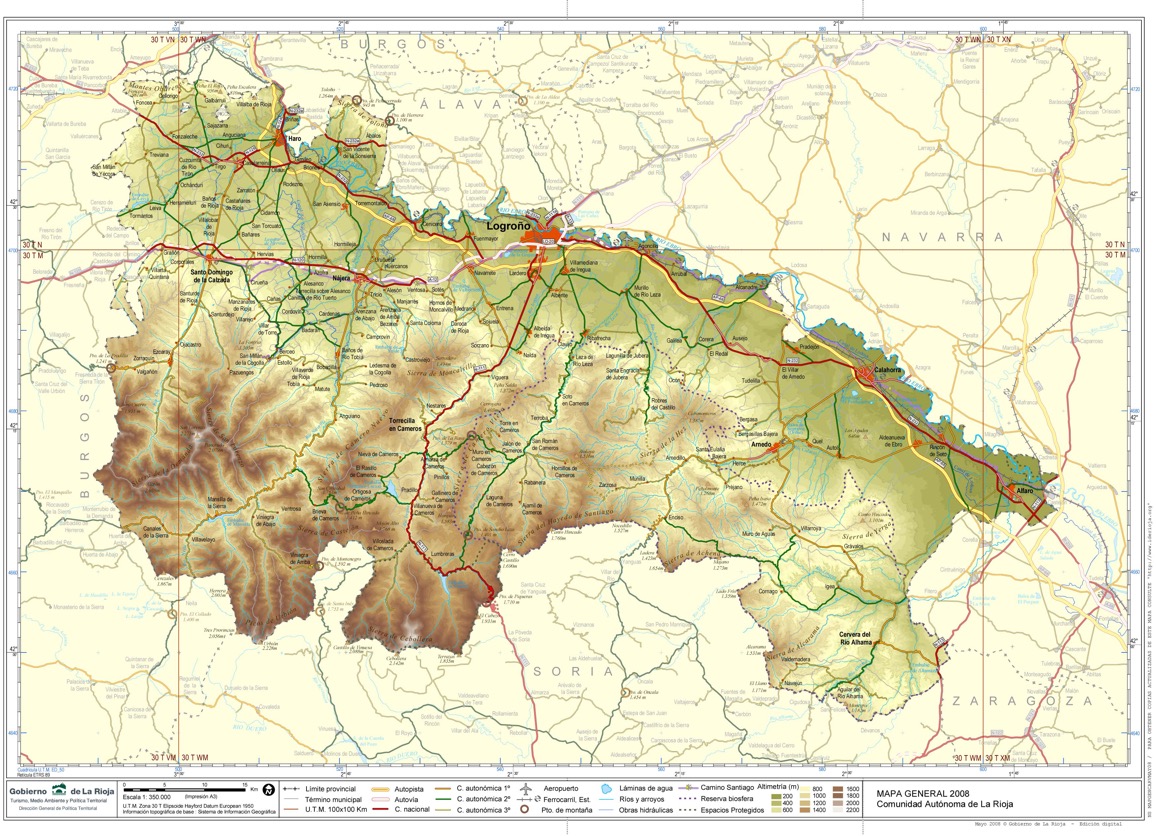

Spain is divided into 17 self-governed regions called comunidades autónomas (autonomous communities), one of them called La Rioja. Wine was so central to its history, culture, and economy that the region took its name from the Rioja wine.

However, the appellation for Rioja wines actually spans three different administrative communities, the main one is La Rioja, the other two being Álava (usually referred to as Rioja Alavesa, in the Basque Country) and Navarra.

It's important to note that there is a difference between La Rioja as a Spanish province and autonomous community and Rioja as a wine region with a denominación de origen calificada (DOCa), the highest category in Spain wine regulations. In fact Rioja wine is made from grapes grown in three different autonomous communities, La Rioja, Navarre, and the Basque province of Álava. So Elciego, home of the Bodegas Marqués de Riscal, produces Rioja wine, but is located in the Basque province of Álava, and not the autonomous community of La Rioja. The distinction between La Rioja province and the Rioja wine region is not easy to understand. For example, the part of Rioja Baja north of Ebro River is in the autonomous community of Navarre, whereas the part of Rioja Alta that encroaches north of the Ebro actually is still part of the autonomous community of La Rioja. But the entire area of Rioja Alavesa is in the Basque Country.

Figures vary, but just the Rioja wine region has nearly 66,000 hectares under cultivation (2020 figures), although I'm not sure if this is just for wine production, or if it also includes grapes for domestic consumption (table grapes) and those that are dried. The Rioja wine region actually produced in 2020 about 268 million litres of wine, so slightly less than Austria (280 million litres) and New Zealand (300 million litres), but more than Greece (220 million litres).

It is often quoted that there are nearly 15,000 grape growers (I presume that means vineyards), and 600 wineries.

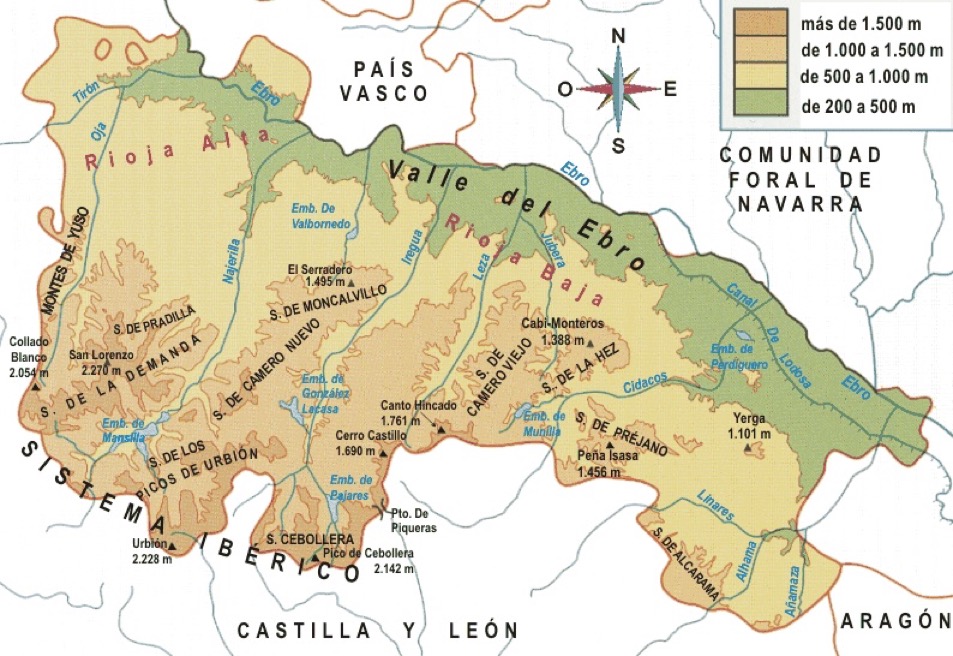

Setting aside the administrative divisions, Rioja is also divided into three wine subregions each with its distinctive character. Rioja Baja (lower Rioja, but now called Rioja Oriental) is the southern and western part, lower in altitude, with a warmer and drier Mediterranean climate. Rioja Alta (Upper Rioja) and Rioja Alavesa (in the province of Álava) are in the northern and eastern part, higher in altitude, with a cooler and wetter Atlantic climate. What we tend to forget is that the three subregions actually make up a valley area on both sides of the Ebro River that is only about 100 km long and with a maximum width of 40 km.

The vineyards are planted on successive terraces and some are located as high as 700 m above sea level. In terms of the soil, Rioja soils are diverse, ranging from clay-limestone, clay-ferrous and alluvial, slightly alkaline, poor in organic content and have moderate water availability during the summer.

Climate change

Such generic statements as warmer/drier or cooler/wetter might have been sufficient 50 years ago, but today everyone, and in particular those involved in viticulture and winemaking, are interested in climate change and the impact it is having and will continue to have on wine production. Generally, across many wine growing regions, climate change has mostly led to regional warming and greater variability in seasonal rainfall. However, despite the global extent of climate change, disregarding regional variations can lead to erroneous generalisations. This is why both the Winkler Index (classification of growing regions based upon growing degree-days) and the Huglin Index (a bioclimatic heat index for vineyards) can be used to more objectively understand climatic variables such as temperature, rainfall, insolation or frost frequency and timing.

Some people might still doubt that our planet is getting warmer, but growers and winemakers in Rioja aren't among them. In a recent study 90% of the 481 growers and winemakers surveyed believe that climate change was a reality. 65% felt that its effects will be negative or very negative and 46% thought that Rioja will have to adapt to new circumstances.

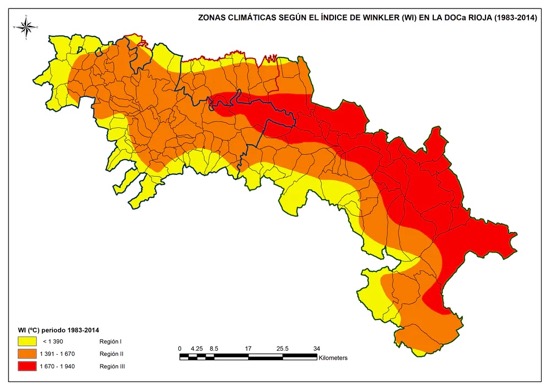

Above we can see a comparison between two sub-periods, 1983-2014 against 1950-1982 for the Rioja region. Most of the region saw a moderate temperature increase of between 0.3 and 0.7 °C for the so-called "growing season temperature". However, in a few areas the temperature increase was more substantial, between 0.7 and 1.1 °C. The nominal growing season is April 1 to October 31, but given that a growing day is a day where the temperature is above 10°C, the season can start earlier or later. Traditionally the season closes in the Rioja region with the Wine Harvest Festival in Logroño, i.e. Fiestas de San Mateo is when people come to town to watch the grape-crushing ceremonies starting on the Saturday before 21 September.

In order to understand better the significance of this temperature increase the Winkler Index is used to classify a region in terms of growing degree-days, i.e. based upon the fact that the development rate of a plant depends upon the daily air temperature above a "zero growth" temperature (10 °C for vines). Growing degrees are the number of degrees above 10° C (for vines), and are accumulated as the season progresses, so in some way they represent a measure of heat accumulation by a plant, which is related to its development rate. The index is just the accumulation of the growing degrees (measured as total °C's) and there are several ranges or classes that correspond to a grapes general ripening capabilities and final wine styles. For example, Bordeaux is classed as Region II (1389-1667 °C), an early and mid-season good quality wine, whereas Rioja is now increasingly classified as Region III (1668-1944 °C), an area of high production for standard to good quality wine.

As a word of warning, the Winkler Index essentially describes the mean daily temperature, but many other important factors contribute to a region's suitability for viticulture (and its terroir) are excluded, e.g. sun exposure, latitude, precipitation, soil conditions, and the risk of extreme weather which might damage grapevines (winter freezes, spring and fall frosts, hail, etc.).

Above we have the Winkler Index for 1950-1982 (a) and 1983-2014 (b) for the Rioja region. We can see the Region II index (orange) and the Region III index (red), which shows a significant warming in the region during the last 60 years. This has important implications for the viticulture of the region, as the grapevine growth cycle has been advanced, leading to earlier phenological stages and changes in ripening dynamics.

The Huglin Index appears to be more widely used in Europe, since it gives more weight to maximum temperatures and uses an adjustment for longer days found in higher latitudes, but the index remains functionally similar to a "growing season average temperature". In Europe, vineyards are found in areas where the average temperature during the ripening season (April-October) is between 12 and 22 °C. The optimal temperature is different for each grape variety, e.g. 15 °C for Pinot Noir, 15.5 °C for Chardonnay, 17.5 °C for Tempranillo, 18 °C for Merlot, 18.2 °C for Grenache, etc.

Above we can see that in the period 1950-1982 (a), the Rioja region had an Huglin Index of 1800-2100, ideally suited to the grape varieties such as Cabernet Sauvignon, Merlot and Syrah, whereas for the period 1983-2014 (b), the region appears more suited to grape varieties such as Grenache (Garnacha Tinta), Carginan (Mazuelo), and Mourvèdre.

On the surface this may not appear too surprising since the varieties authorised for red Rioja are Tempranillo, Garnacha Tinta, Graciano, Mazuelo, and Maturana Tinta (Trousseau). However, there are variations in the reporting of the Huglin Index for different grape varieties, and in particular Tempranillo is often associated with a lower index.

Interestingly the growing season precipitation in the Rioja region over the entire period 1950 to 2012 did not change significantly, even if the area associated with a slightly lower rainfall did grow over time.

(decoupling of technological vs phenolic ripening in red cultivars, which are predominantly planted in this region)

This could also impact some adaptation measures as changing the varieties of new plantings. In this regard, cultivars of longer ripening cycles, such as Graciano or Carignan could be preferred to widely planted Tempranillo in some areas. In this regard, it is worth remembering that strict regulations about the grapevine varieties that are allowed for planting and winemaking in the Rioja Wine Appellation, with restrictions in terms of yield and some viticultural practices, such as pruning, exist. This implies that any given modification or action to adapt to this observed warming has to meet all these regulations. Among other measures, some growers have started to explore plots at higher altitudes.

https://climadjust.com/blog/la-rioja-a-wine-region-under-a-changing-climate

https://www.greatwinecapitals.com/wine-stories/how-climate-change-is-impacting-the-harvest-in-rioja/

https://www.foodswinesfromspain.com/spanishfoodwine/global/whats-new/features/feature-detail/spain-2020-wine-harvest.html

https://winereviewonline.com/printArticle.cfm?articleID=647

https://bodegaslan.com/en/the-growth-cycle-at-vina-lanciano/

Rioja wines themselves are classified according to the time they have been aged, mainly in casks (it can vary for white and rosé wines). Vino joven (literally “young wine”), is normally un-oaked, from the most recent vintage, and made to be consumed young (it can also be labelled sin crianza). Vino de crianza has to be aged for two years, at least one year in oak casks. Reserva has to be aged for three years, again at least one of them in oak casks. To qualify as Gran Reserva, the wine has to be aged for no less than five years, and at least two of them in casks.

in the good old days, the better grapes were saved for the higher categories, which were generally worth their higher prices. But the system was gradually perverted by poorly made wines bearing gran reserva or reserva labels. nowadays, many producers seek only generic or joven labels for all their wines, not wanting to be subject to what they regard as restrictive regulations.

whites have played only a small role here for many years (only 7 percent of the vineyards are planted to white varieties), but because interest in whites in general is growing, we are now seeing some interesting developments. (For a detailed discussion of white Rioja, see wfw 20, pp.116–21.) there’s also a little rosé (rosado), but Rioja is overwhelmingly red.

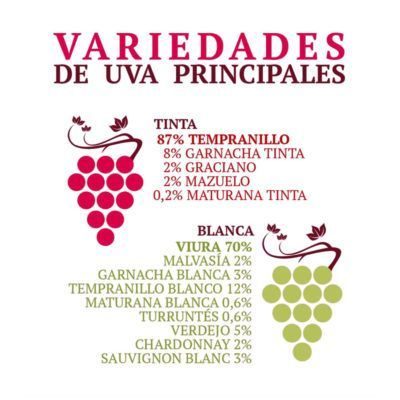

Until 2008, there were only four red varieties employed by Rioja, i.e. Tempranillo, covering about 80% of the productive vineyards, Garnacha, Mazuelo (known as Cariñena or Carignan in other regions) and Graciano. As a word of warning, many lesser known varieties have many local synonyms, and even a few of them are in fact mistaken synonyms.

In March 2008, another three red varieties (and six white) were authorised, i.e. Maturana Tinta, Maturana Parda (both old, recovered varieties), and Monastel (not to be confused with Monastrell or Mourvèdre). Monastel from Rioja is the same grape grown in Somontano as Moristel, which is also called juan ibáñez in the south of aragón. ???

In addition there are also“international” varieties such as Cabernet Sauvignon, which is in some ways more indigenous to Rioja than is Garnacha, since Marqués de Riscal planted it almost 150 years ago, whereas Garnacha only made its appearance after phylloxera, some 50 years later.

It is commonly recognised that the quality, and thus the prestige, of Rioja wines declined in the 1970's.

Experts suggested that this was because vineyards were planted with younger, higher-yielding vines, and coupled with a less rigorous selection and sorting, meant a rapid decrease in the quality of the grapes. Add to that the increasing use of industrial techniques designed to favour shorted maceration cycles of barely mature fruit (to avoid high alcohol content) produced low-quality must, without the aromatic compounds, concentration, or tannins that could withstand ageing in oak casks. As a result, many of the wines were acidic, thin, and dried out.

One explanation was that bodegas didn’t have vineyards of their own, relying on grape growers to supply them. This created a conflict of interests, because the growers, paid by the kilo, had very little interest in the quality of the grapes, concentrating instead on quantity, while wineries hoped their suppliers would do the opposite. Some of these wineries were nothing more than wine factories, and the bottles coming out of them during the 1970's and 1980's gave Rioja wine a bad name. Today most wineries believe that the ownership of vineyards and full control of viticulture are critical for their wines.

There were a few bodegas that experimented with longer macerations, shorter maturation in barrels, and French oak casks. Relevant milestones were the creation of Marqués de Cáceres and Contino, which pioneered the single-vineyard concept as early as the 1970's, producing wines that were darker and fruitier than the average Rioja.

In the late 1980's and early 1990's there was a noticeable move to improve the quality of the Rioja wines, by using terms such as "alta" to differentiate themselves from the poorer quality wines. Looking back people now thinks that the mistake was to continue to use mediocre grapes, and try to use the oak casks to add aromas to the wine. To underline this "better" wine they put it in a heavy bottle and added a higher price tag, but they did not address the underlying problem.

But also in the 1990's boutique, or garage, wineries started to appear, creating a renewed focus on quality grapes by some other small, artisanal producers. Many moved away from the bad practices of the 1970's and 1980's, and some returned to the older traditions. Others looked for more colour, fruit, and freshness, through longer macerations and the use of French oak casks. Many even abandoned the traditional designations of crianza, reserva, and gran reserva.

At the time there was much critical acclaim for Pingus (a Ribera del Duero wine), with a so-called 200 % new-wood treatment. Many Rioja bodegas copied the idea, but by going too far, produced an overripe, over-extraced, and over-oaked, very dark heavy, almost jammy, wine.

Fortunately by 2001 the pendulum swinging back, and producers started to focus on acidity, balance, and finesse, and not just colour, alcohol content and dense aromas. The move can be seen as a return to the style of the more traditional wines, with a focus on the character and the terroir of Rioja. However, there is a trend to drink wines that a too young, and many people, including Spanish consumers, don't lie down (store) their wines. Traditionally wine was aged by the winery and released when ready, but traditional wine making techniques make it difficult to know what a young wine should taste like, because they were never released as such.

The key today is to focus on balance and finesse in wines, even though aromatic compounds might be a little more concentrated than in the past. Producers consider owning their own vineyards the essential prerequisite for quality, and they look back at tradition whilst exploiting modern technology.

For readers who might want to follow up on my superficial summary, I can recommend looking at the following wineries:-

López de Heredia

Bodegas Muga, including Torre Muga, Aro and Prado Enea

Artadi, including El Pison

Bodegas Contador

Eguren Ugarte

Finca Valpiedra

Remírez de Gamuza

Palacios - Remondo

Bodegas Roda

Señorío de San Vicente

Viña Ijalba.

And if you are looking for a hotel that is typical of the region, checkout the very decent 2-star Castillo El Collado.

https://enoviti-hanumangirl.blogspot.com/2021/01/farm-winery-layout.html

https://www.materialsperformance.com/articles/material-selection-design/2015/09/wineries-equipment-materials-and-corrosion

https://www.archdaily.com/168716/wbf-lab-flad-architects/5015b13e28ba0d5a4b000a33-wbf-lab-flad-architects-winery-diagram

https://www.tlcd.com/design/justin-j-lohr-center-for-wine-and-viticulture-cal-poly-san-luis-obispo/

https://www.archdaily.com/168716/wbf-lab-flad-architects/5015b15a28ba0d5a4b000a34-wbf-lab-flad-architects-floor-plan

https://rmi.ucdavis.edu/about

https://architizer.com/projects/martins-lane-winery/

https://www.archdaily.com/397667/ixsir-winery-raed-abillama-architects/51d45563b3fc4b58340001ce-ixsir-winery-raed-abillama-architects-diagram

https://ihmkolkatafoodandbeveragenotes.blogspot.com/2018/04/wine.html

https://www.pall.com/en/food-beverage/wine.html

https://en.paperblog.com/from-italy-with-wine-wine-production-process-1702467/

https://www.winemag.com/2019/10/08/how-red-wine-is-made/

20Winemaking and facility design “Wine means the product obtained exclusively from total or partial alcoholic fermentation of fresh grapes, crushed or otherwise, or of grape must,” according to EU wine regulations. The basic princi-ple of winemaking has not changed substantially since ancient times, when people crushed grapes by stomping on them with their bare feet. In our high-tech era, however, the aid of physical, chemi-cal and technological processes is enlisted to opti-mize and streamline wine production and to make the resulting drink an incomparably better product. Aspects such as sustainability and environmental considerations are playing an increasingly important role in this process.The contrast between the ancient and the modern practice of wine production is therefore considera-ble. Must production and pressing used to be accomplished in one step, as the grapes were trampled in a basin with a drain to let the resulting juice run off. In ancient Egypt, grapes and skins would be pressed a second time in sacks. Filled into earthenware containers, the juice fermented spontaneously or was boiled. Certain herbs were added and the wine was often watered down before drinking. While these rather primitive methods have long been consigned to history, a few processes, such as spontaneous fermentation, are being rediscov-ered by some winemakers. Other vintners eschew all chemical processing of their wines. Still others try combining old and new methods in various ways. In short, the process of wine production is a highly heterogeneous one. The differences in approach already become appar-ent during grape receiving and processing. The first step to promoting quality is the grape selection, which is particularly important in the processing of red grapes. During selection, mouldy and unripe grapes, and particularly the remains of leaves and stems, are removed from the fruit either manually at the sorting table or sorting belt, or with the help of automated sorting facilities. This step in the pro-cess occurs together with destemming, a process by which the grapes are separated from the rachis. Today, the selection and destemming, like the crushing or maceration of grapes, no longer takes place at the vineyard but primarily inside the winery itself.MacerationTo start the process of maceration, the crusher gently tears the grapes open and crushes them without breaking the seeds, which would add their tannins and bitters to the end product. The result-ing thick mixture of fruit pulp, grape seeds, skins and juice is called the must. The less the must is exposed to oxygen, the smaller the danger of oxi-dation (browning). This is prevented by adding sul-phur dioxide or carbon dioxide. The length of time the red wine is permitted to stay in contact with the skins and seeds depends on the characteristics and quality of the harvest. Extended maceration or extraction can result in a full-bodied wine, but it could also intensify unwanted tannins and pig-ments. As a general rule of thumb, maceration should be about as long as the fermentation pro-cess; depending on the desired style of wine, how-ever, it could also last a bit longer.PressingIn the making of white wine, the pressing occurs right after crushing to separate the grape juice from the solids in the must. To this end, most wineries use pneumatic, hydraulic or mechanical presses. Modern presses can be set to regulate the pressing intensity and duration, which, depending on the type of wine, takes between one and a maximum of three hours. Varying according to the variety, ripeness and vintage of the grapes, between 65 and 80 litres of juice can be retrieved from 100 kilo-grams of grapes. Red wine grapes used to make rosé go straight into the press after crushing, with-out maceration and without a heating of the must. Immediate pressing gives the wine its characteristic light red colour, as only a little pigmentation from the grape skins leaches into the wine.The solids remaining after the pressing, called pom-ace, can be used to make pomace wine or pom-ace brandy (such as marc or grappa), the quality of which improves with storage length. One hundred kilograms of pomace can yield about seven to nine litres of brandy. Often the must is clarified by vari-ous methods (sedimentation, flotation, filtration, fin-ing) before pressing, in order to remove the insolu-ble matter.

——

These Bordeaux method in winemaking or methods begin as soon as the vine is cultivated. We select the grape varieties best suited to the local conditions of soil and climate. We sort and reproduce the best plants, by provignage or by grafting. The vine is pruned using certain methods. The grapes are harvested at maturity, which sometimes involves several passages in the vines or even spreading the harvest depending on the exposure of the plots10. Then it is transported with precaution and without delay to the presses, in order to limit its oxidation.

During wine making, the stalk is separated from the grains before pressing. Fermentation is carried out in one go, whereas in Rioja grapes were added to vats where previously harvested grapes were already fermented, which seriously affected the homogeneity of this fermentation11. Topping up is then made in the tanks, to avoid contact with air as much as possible. Once the wine has been placed in barrels, regular racking is carried out to remove the lees and impurities from the wine, and frequent topping to prevent oxidation. The wine is then clarified, often using egg white12, and the duration of ageing in barrels is programmed according to the characteristics of the wine.-

——————

The wine sector in the Basque Country has experienced a boost in production and sales in recent years of such magnitude that it makes it the most dynamic and internationally recognized within the Basque agri-food industry. The production of grapes, wine and txakoli in 2003 amounted to a total of 270 million euros. It maintains 2,017 direct jobs, according to data from the Department of Agriculture and Fisheries of the Basque Government for 2002, which is equivalent to 12.68% of the personnel working in the Basque agri-food sector, which amounts to 15,910 employees. These direct jobs have not taken into account the approximately 2,000 workers who at the time of harvest and temporarily dedicate themselves to picking grapes.

In 2003, Rioja Alavesa produced 79,724,174 liters of wine, which represents 27% of the total wine with De-

Rioja Origin nomination. A total of 71,995,520 liters were sold in 2003, of which 54,890,941 liters were destined for the domestic market and 17,104,579 liters for the foreign market. Just five years ago, 56,435,072 liters were marketed. Of these, 39,682,979 were placed in the domestic market and the rest, 16,752,093, abroad.

The growth of recent years has been accompanied by some vintages that obtained the qualifications of “excellent” in the years 1994, 1995 and 2001; “very good” in the years 1996 and 1998 and “good”. during the years 1993, 1997, 1999 and 2000. The young wine, once the majority in this region, has given way to crianza, reserva and gran reserva wines, which already account for about 50% of the total production and that generate greater added value and more social recognition.

The txakoli also multiplies its production

The three areas with Denomination of Origin –Arabako Txakolina, Bizkaiko Txakolina and Getariako Txakolina- have also multiplied the production of txakoli each year. Thus, in Bizkaia around one million kilos of grapes were harvested - 30% more than in the 2002 harvest - with which 725,000 liters were obtained. In the third harvest since its declaration as Denomination of Origin, Arabako Txakolina extracted 195,000 liters of broth. In Gipuzkoa the increase was around 40% compared to 2002.

In the last decade, the area dedicated to the planting of vineyards in Rioja Alavesa has gone from 8,039 hectares to 12,726, according to data from the Regulatory Council of the Denomination of Origin of Rioja, which is equivalent to an increase in 58.30%. The one destined to the txako- lis of Álava, Bizkaia and Getaria is 400 hectares.

Among the fifteen municipalities of Rioja Alavesa there are 261 wineries associated with the Rioja Qualified Denomination of Origin. The highest concentration occurs in Laguardia with 48, Villanueva de Álava with 43 and Lapuebla de Labarca with 41.

The main buyers of Rioja wines are the United Kingdom, Germany, Switzerland, the United States, Sweden, the Netherlands, Denmark, Mexico, Norway and France. In recent years there has been a continuous increase in the demand for Rioja, both in the United States and in Mexico, and exports to the rest of the countries mentioned have been practically the same, with some fluctuations. France is the only one of these European countries that increased the level of imports of Rioja wines in 2003 compared to the previous year.

With regard to the consumption of wine in the state market, according to the MAPYA Annual Report “Food in Spain” corresponding to the year 2002 (last to date), in the chapter corresponding to the consumption of alcoholic beverages, It is found that although total wine consumption (in liters, per person and year) has decreased by 3% compared to the previous year, Denomination of Origin wines have increased by 1% during that year. During 2002 the consumption of wines with Denomination of Origin has meant a

27% of total wine consumption (table wine, sparkling ...). However, if the prices are analyzed, it can be seen that the trend is the opposite: the price of wines with Denomination of origin has fallen by 1.5%, while that of wine in general has increased by 5% .

LITERS MARKED FROM RIOJA ALAVESA IN 2003

Sin crianza

Without ageing Aging 27,496,248 liters

Crianza 29,147,449 liters

Reservation 12,981,098 liters

Gran reserva 2,370,725 liters

Total 71,995,520 liters

GLOSSARY

Crianza Aging: wine that is at least two calendar years old and one of them has remained in the barrel.

Reserva: red wine that has been aged for three years in the winery and of these, one has remained bottled. It is also the white or rosé wine that has been aged for at least six months in the barrel and another 18 months in the barrel.

Gran Reserva: red wine that has been aged for at least two years in barrels and another three in bottles; white wine with a minimum of six months in the barrel and the rest to complete the four years in the bottle; cava that has had an ageing process of more than 30 months.

———

Another important adaptation, to the point of leading to a fundamental difference with the original Bordeaux reference, is the domination of the sector by these large bodegas21. A few figures from 201422 will allow us to better perceive the concentration of the processing sector23. Of the 509 wineries registered under the appellation (DO Ca.) Rioja:

- the 4 most important market more than 10 million liters each, and represent 23% of the total volume;

- the next 10 sell between 5 and 10 million liters each, and account for 28.4% of the total;

- 37 each sell between 1 and 5 million liters and represent 29% of the total;

- 26 each sell between 0.5 and 1 million liters and account for 6.6%

- 432 finally sell less than 500,000 liters each and account for 13%.

In cumulative sales percentages, it emerges that 14 players represent more than half

of the total sales and that 51 (or 10% of the players) sell 80% of the total, which indicates a considerable concentration.

Why do these bodegas have such dimensions and handle such volumes? In large part because the gradual implementation of the current economic model took place in a context different from that of Bordeaux, which we were supposed to emulate from the start. In Bordeaux, for centuries and until the middle of the 20th century, the central and dominant actor is the "trader", also called "trader-breeder". négociant », appelé aussi « négociant-éleveur ».

The Bordeaux merchant-négociant then buys the wines of various producers, classified grand crus or others, stores them in his cellars, raises them, blends them if necessary, and takes care of their marketing24. The producer therefore does not really need large facilities, intended to store several years of harvest, in barrels and then in bottles, since his wine leaves the property fairly quickly. In short: in Bordeaux, the winegrower cultivates the vines, makes the wine and sells it to the merchants, who are responsible for maturing it, possibly keeping it in the cellar for a certain time, and marketing it.

In Rioja, this link in the chain that constitutes the trader does not exist, and the profession is therefore organized in a different way. The winegrower cultivates the vines, harvests the grapes and his role ends there. In fact, he delivers his grapes to a bodega, industrial and private, most often25. The bodega, whose production capacity can be enormous, as we have seen (the largest26 reaches 30 million liters per year ...), therefore buys the grapes from the winegrower, makes the wine, raises it, assembles, markets and takes care of communication, in order to ensure its national and international reputation.

As we can see, because of this specific distribution of roles between the players in the sector and this domination by a few large structures, the very organization of the Rioja wine sector and the economic model in place are totally different from that of Bordeaux.

A third point seems fundamental to us, it is the use made of the Bordeaux barrel and the importance given to it. La Rioja certainly imports the systematic use of barrels from Bordeaux, at least for higher-end wines. But the Rioja bodegas ultimately make a different and original use of barrels. The ageing times in barrels are almost systematically extended compared to Bordeaux practices, and in particular for the high-end wines of Reserva and Gran Reserva. And above all, by pushing the Bordeaux logic of wine maturing further, the practice has become widely used to then keep the wine in the bodega, in the bottle, for many years before putting it on the market. Without going as far as the extreme case of López de Heredia (Viña Tondonia, in Haro) which has made a specialty of marketing wines of 10 years of age and over, we can mention the Viña Ardanza, Reserva wine from the bodega La Rioja Alta, from Haro, whose vintage available in 2014 was ... 2005, the following years will not go on sale until later.

The combination of this sort of sacralization of long ageing, and especially of the prolonged passage of wine in barrels, with the local perception of the terroir (understood at the level of the Denominación de Origen and not of the precise plots of grape production) has as corollary, and as a consequence, a system of hierarchization of wines totally different from that of Bordeaux (and of France in general, where the classifications depend on the cadastral and even plot origin of the grape): in Rioja (as in many Spanish wine regions) the hierarchy, from bottom to top, consists of four categories: Joven, Crianza, Reserva and Gran Reserva, established according to the time that the wine has spent in barrels and then in bottles in the bodega, before being marketed. It is therefore the length of ageing that conditions access to each of the categories: the longer the length of ageing, the higher the wine is in the hierarchy (provided naturally that the wine at the start has sufficient qualities to withstand this prolonged passage in the wood with profit).

This particular context has important effects on the sale and marketing of wine: in fact, Rioja wine is ready to drink when it is placed on the market. The contrast is marked with the Bordeaux en primeur sales system, where the buyer reserves and pays for the wine before it is even available, while most of his ageing remains to be done, and he will often have to wait afterwards. years before consuming it.

When we talk about the sanctification of the barrel, the word is not too strong: the communication of the bodegas (whether on their websites, or during cellar visits) systematically insists on the number of barrels in the cellar: 10,000, 20,000, up to 70,000 for Juan Alcorta Campo Viejo, in Logroño. And DO Calificada Rioja is proud to be the first region in the world for the number of barrels: more than 1,284,000 in 2014.

Finally, let us note a final opposition with the Bordeaux model: the clear desire of Rioja, and more and more asserted over time, to be a direct competitor of Bordeaux, by the very quality of its wines, by their positioning in the main markets. export, and perhaps above all through the display of a certain luxury, a certain standard of facilities, impressive and sometimes even somewhat conspicuous. Still, these large cellars, these large Rioja bodegas have been, for 150 years, but especially for ten years, with the development of wine tourism27, one of the major and most visible elements of the identity of the vineyards and wines of Rioja, of the inter-profession and of the region as a whole.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the “Bordeaux generation”, that is to say the one who adopted and implemented the techniques in use in Bordeaux, made an essential contribution to the construction of the identity of the vineyards and the wines of Rioja. .

The reference to Bordeaux has largely helped to anchor this vineyard and this wine among the great vineyards and the great wines of the world, throughout the period when the Rioja had to make its place. And this, both for internal and external use.

On the other hand, for one or two decades, this influence, without being denied, has been relatively ignored: Rioja is now asserting itself as a great wine in its own right, with its peculiarities and qualities, which are moreover real. and indisputable, and which are recognized, valued by consumers, and validated by major global influencers, including those of the Parker movement.

Indeed, as we have seen, the model put in place is certainly inspired in part by that in force in Bordeaux in the 19th century, but it has developed specific aspects to the point of leading to wines that are also specific, because of the systematic and prolonged use of barrels, because of the volumes treated, often considerable, because of the culture of regularity (in a brand logic28, rather than terroir or micro terroir29, French and Bordeaux), finally because of the criteria for ranking the wines.

Nowadays, the Bordeaux influence is perceived and presented locally as a part of the history of Rioja vitivinicole, but clearly stemming from a past that has become distant.

……..

—

The Heirs of the Marqués de Riscal, wine mathematicians

It is very difficult to find a better visit than this for the summer, and almost impossible to taste a tastier wine

The Marqués de Riscal hotel, seen from its vineyards.

The Marqués de Riscal hotel, seen from its vineyards.COMOREBI.STUDIO

ALFONSO MASOLIVER

CREATED 07.25-2020 | 10:12 H

/

LAST UPDATE. 25-07-2020 | 10:34 H

Among the fresh vineyards colored by a deafening glaucous, striding with tradition and flavor through the lowlands of Rioja Alavesa, no visitor can avoid discovering a brilliance rising a hundred meters above the ground. Dim at first, it intensifies as we get closer. Slowly the hues of radiance, of pure steel and red wine, fade, covering the surrounding vines with a generous layer chiseled with rays of the sun. The most knowledgeable will be able to recognize this building, taken from the world of dreams through the mediation of the expert hand of Frank Gehry - known in our country for being the architect of the Guggenheim Bilbao - and they will know that its steps are already approaching the historic Marqués winery. of Riscal.

As hypnotized by the fantastic vision of the building, we are drawn to the entrance of the cellar, like a moth enraptured by the light from a window, and our desires howl at us a gift, a whim. What is it like to cross those doors, visit this monumental winery and taste its aromatic wine that emanates from the land itself.

Among the 10 most admired wine brands in the world

When Don Camilo Hurtado de Amézaga, Marqués de Riscal, was commissioned by the Álava Provincial Council to hire a winemaker to introduce the growers of the area to the techniques used in the Médoc, in order to make wines according to under the French system, two options were presented to him: to produce large quantities of an acceptable, fragrant wine with strong flavors; or squeeze the best grapes from his vineyards one by one, until reaching an excellent wine whose flavor would persist in the mouths of all who tried it. It was the year 1858 when he chose the option of excellence.

One of the wineries, built in the Bordeaux style in 1883.

One of the wineries, built in the Bordeaux style in 1883.COMOREBI.STUDIO

D. Camilo contacted Jean Pineau, winemaker at Château Lanessan. Without giving importance to the high costs of the operation, convinced of the success of his company where everyone had preferred to abandon the project, he built the first building of his warehouse. It still stands, and inside is La Catedral, a unique collection made up of bottles from all the vintages produced by the winery from its first, in 1862, to the present day. It is an underground treasure hidden under a maze of vines. It is a dark jewel, damp and clean of dust, crouched in front of the visitor's eyes.

The rest is history. One vintage after another could be achieved one of the best wines in the world, until in 2019, Drinks International categorized Marqués de Riscal as one of the most admired wine brands in the world. We are talking about a Pulitzer of wines, with an Oscar for best screenplay. From its classic reserve to its new 100% organic Verdejo - in which no type of pesticides or chemical fertilizers have been used - the renewal and adaptation to the complicated world order have allowed this brand to navigate year after year upright on the waves.

A dream visit

French oak barrels with a treasure kept inside.

French oak barrels with a treasure kept inside.COMOREBI.STUDIO

Each step in the visit to the winery is marked by a new color, a new aroma, leading us by the hand to the deepest layers of the world of wine, which is, in short, a world of dreamers who managed to fulfill their dreams. What name does a dream come true? Rosé, crianza, reserva, gran reserva. Each of them harvested from the vines based on their age. Thus, rosé is made from young vines, under 15 years of age; the crianza with those who are between 15 and 40 years old; the grand reserve from the age of 70 ... until reaching the oldest vine of the Marqués de Riscal, a nice spinster born in 1902 who only delivers her grapes to make the best wine a mortal can taste.

A maximum of 5,500 kilos of grapes collected per hectare go through an elaborate process until they finish on the palate. The leftover grape is used as fertilizer, the leftover from the barrel is sold for the production of pomace or served in the wine therapies of your hotel, every detail of the fruit is used because she is the spoiled child of the Marquis and his heirs. Its fermented juice rests for years (two for the reserve, three for the great reserve) in oak barrels hidden in the sunlight, they are labeled when they receive an order and they fly, like pieces of bottled dreams, straight to the minds of the consumer. .

Around 4 million bottles roam every year in one hundred countries of the world, each one made with mathematical precision. Filling gaps. 130,000 are still kept in the Cathedral, like crown jewels ready to look at and not touch.

The most awaited moment: the tasting.

The most awaited moment: the tasting.COMOREBI.STUDIO

At the time of the tasting - which due to the coronavirus is done with each individual leaning on his own barrel, always respecting safety distances -, waited throughout the visit with a childlike desire, three wines are placed very upright in front of to us: an organic Verdejo from 2019, a Marqués de Arienzo Crianza from 2016 and a Reserva from 2015. They don't give it to you with cheese here, which is when they serve you the wine with cheese to hide its poor flavor. They give it to you with chorizo and Riojan salchichón, soft so as not to steal an iota of the flavors of the liquid. And these flavors I cannot describe, nor do I want to. They will be a different experience in each one.

——

Camilo Hurtado de Amézaga, 6th Marqués de Riscal, was considered to be the creator of the cellars named after the heirs of Marquesado du Riscaln 1. He was residing in Bordeaux when he received a commission from the County Council of Álava d ' hire a winegrower who could teach the region's harvesters the techniques used in the Médoc, to produce wine according to the French system. The chosen one was Jean Pineau, master winegrower of the cellars of Château Lanessan, with who signed, representing at the Deputation, a contract to advise the producers of Alava. Hurtado immediately sent to Rioja Alavaise, wine of Cabernet Sauvignon, Merlot, Malbec and Pinot Noir, the finest grown in France, to test them in his vineyards, where grapes of the Tempranillo and Graciano varieties were grown. .

In 1858, Hurtado who had inherited from his father a few cellars in Elciego, founded the Marqués de Riscal cellars by applying the techniques used in France, and hired Pineau, who had stopped working. In 1895, at the International Exhibition in Bordeaux, Marqués de Riscal became the first non-French cellar to receive the Diplôme d'Honneur5.

Marqués De Riscal brought many innovations to the industry of the time, as well as the metal mesh which covered the bottles, (intended to prevent them from being fraudulently filled and which brought a luxurious character), wooden cones fermentation, use of barrels of 225 liters or bottles in a horizontal position 6. In the 1920s, some 238,000 bottles of different years were stored in the cellar, being the establishment with the best quantity of old vintages in the world.

From the 1970s, the company decided to diversify its production and bet on the development of other varieties of wine. Thus, after two years of testing, in 1972, it began producing white wine in its new cellar in Rueda (Valladolid) 7. The success of production in this area attracted new investors, and in 1980 it led to the creation of the appellation of Rueda4.

City of Wine [edit | modify the code]

As part of its strategic plan in the 2000s, the company is moving towards a more avant-garde cellar model and with more vocation as a leisure complex, called Ville du Vin. Thus, she remodels the entire environment and builds a new cellar with the most advanced technology, in addition to new bottle racks and new laboratories.

The bet of leisure is located mainly in the new building designed by Frank Gehry (known for the Guggenheim Museum Bilbao), an avant-garde construction that has become the symbol of Marqués de Riscal. This building, built in sandstone and a titanium roof, houses a hotel of the Starwood Hotels & Resorts chain and two restaurants, the Bistró 1860 and the Marqués de Riscal, awarded in 2011 with a Michelin Star. The cover of the hotel aims to represent the red wine (pink color), the characteristic golden mesh of the Marqués de Riscal bottles (gold) and the bottle caps (silver) 8.

Vineyards [edit | modify the code]

The company's wine production spans a vast extension of vineyards. Marqués De Riscal has 1,500 hectares of vineyards in the Rioja area in Elciego, Leza, Laguardia and Villabuena d'Álava, of which 500 are owned and 985 controlled9. In the Rueda area, it has the largest owned vineyard in the entire D.O., with 205 in the municipality of Rueda. It has 250 more in the rental of Rueda, La Seca, Serrada and Rodilana7. In addition, it has 200 in the municipalities of Zamora de Toro and San Román de Hornija, from which the red of the land of Castile and Leon is produced10.

Production [edit | modify the code]

Bottles of Baron de Chirel Reserve 2001, made from 85% Tempranillo grapes and 15% other varieties. This wine matures for 21 months in barrels and a minimum of 12 months in bottle11.

The brand invoices around 50 million € / year and exports to 104 countries around the world. It launches around 7,000,000 bottles of red and white, in addition to 200,000 of Laurent Perrier sparkling wine12.

Marqués de Riscal markets red wine with the Frank Gehry Selection 2001, Baron de Chirel, Marqués de Riscal 150th Anniversary, Marqués de Riscal Grande Réserve, Torrea Estate, Marqués de Riscal Réserve, Marqués de Riscal Rosado and Marqués de Arienzo labels5 labels.

The white wine is made up of the Marqués de Riscal Limousin, Montico Property, Marqués de Riscal Sauvignon Blanc and Marqués de Riscal Roule Verdejo brands.

In addition, Vins du Terroir de Castille-et-Léon sells Riscal 1860, the only red that it produces outside of La Rioja.

The Marqués de Riscal winery was created in 1858, and produced it first bottle in 1862. The first extension, El Palomar, was built in 1883 (additions made also in 1968 and 2000).

1972 Marqués de Riscal white wine from the commune of Rueda in the Castille-et-León.

1986 Barón de Chirel

2007 Marqués de Arienzo

Marqués de Riscal gras are grown over 1,500 hectares, in Elciego, Leza, Lagiardia and Villabuena. The soil is poor, being rich in clay-lime.

In the original cellar there is "the cathedral", home to bottles of all the vintages since 1862.

https://www.wine-searcher.com/wine-label-spain

https://www.decanter.com/spanish-fine-wine/read-spanish-wine-label-384254/

Growing Conditions

A hot autumn with hardly any frosts and very little rainfall.

With the arrival of winter the weather switched completely with a succession of heavy precipitations (some in the form of snow) and frosts which reached down to 9ºC below zero. Budbreak began around the 15 April, a month when big temperature rises were registered reaching similar levels to the summer, leading to a spurt in the vines development.

The véraison started on 30 July. The summer was extremely dry and it was not until the seconnd fortnight in September that moderate rainfall (15 litres/m2) was recorded. Harvesting began on 27 September. The resulting harvest showed unusually high levels of probable alcoholic strength and of colour-related compounds. The growth cycle lasted a total of 205 days.

Booking 9.2 (fantastic) 305

Tripadvisor 4.5/5 1271 reviews

Breakfast seemed not up to the level of quality of this hotel. Presentation, variety and taste need improvement.

We had a nice stay at Marques de Riscal but for me, it didn't have the feel of a luxury hotel, more of a conveyor belt for tourists who wanted to spend the night in a Gehry building (yes, I was one of those said tourists). The food in the bistro restaurant was fine, but not really much to write home about and definitely overpriced.

The staff were all very kind and professional and clearly take pride in working there. The small complementary bottle of wine in the room was nice and the big windows in the rooms were nice to enjoy the view. The spa was great and the wine scrub and massage we both had was really excellent and worth the money. They were welcoming of our baby which was nice. The setting of the hotel and views are stunning as is the outside of the property obviously.

Disliked

· Look, it's a stunning hotel from the outside but sadly does kind of just feel like a Marriott corporate hotel on the inside, a little soulless to be honest and it's incredibly expensive with that in mind. The bar and library were just a bit...cold I guess. The library smelled a little weird and had no atmosphere so there were not many inviting places to enjoy a glass of wine. We ended up finding a spot in the vineyard itself to enjoy the sunset. The spa and the vineyard setting were really the best bit so we might have got just as much out of the visit but just coming for a spa day and a glass of wine (not sure if they allow this). We ate lunch in the traditional restaurant and had a great wine recommendation from the sommelier (not a Marques De Riscal wine of which there is minimal choice - it's a small vineyard.) Lunch was a bit rich and stiff and we didn't love the food to be honest though the views were nice. They are constructing a new wing of the hotel over the spa so the noise was a bit distracting as well. The wine tour was nice and the cellar interesting but the tasting was one of the most boring I have done in a while - only 2 lower end M de R wines to try - one white and one red, nothing very interesting. I would have rather had a longer tasting with different levels of the wines and more info even if this meant smaller quantities. Overall we were very happy we only booked one night and would not necessarily recommend others stay overnight though a visit to the spa or a stop for a glass of wine would be very worthwhile. They could do with making it cosier inside, the food simpler but better and focussing on people wanting to enjoy delicious wine in a great and relaxed setting with more and cosier breakout areas to sit or encouraging people to see the sunset from within the vineyard itself.

The hotels location was superb and the rooms beautiful and very well equipped,staff very helpful and professional,but only to be expected when in such a high profile and expensive hotel.

Disliked

· Time to replace the bathroom towels,looking jaded.Restaurant staff could be slightly less efficient i.e. not remove plates as last morcel of food has found its way into the mouth and could be a little more human super efficient robots are not what guests require in a hotel of such quality.

We were looking forward to visiting Rioja and seeing this unusual Hotel. It fulfils its aims of introducing you to the Margues De Riscal wines. The wine tasting trip was informative and generous in measure.

Beautiful views of surrounding countryside and lovely open terraces for eating and drinking.

The spa area was very good indeed with plenty of space to relax.

Disliked

· The restaurants are more suited to groups, being relatively bright and slightly lacking in atmosphere. The Spanish Bistro was really disappointing both food and atmosphere. 1860 was better but you do feel slightly processed.

Overall for us the the experience did not live up to the billing or the price.

The staff were amazingly attentive. Otherwise the hotel, facilities, food, wine, location, architecture and general ambiance is second to none. We love this place!

The wine tour was simply fascinating and provides real insight into the production of the most delicious Rioja.

The views surrounding the hotel are breathtaking and the location offers quick access to Laguardia, which is delightful and adds an authenticity to the stay.

Disliked

· The variability of prices of the same wine throughout is a little disconcerting. The food is a little overpriced and the breakfast menu in the restaurant not as expansive as I'd like.

Hard to reach location requiring expensive taxis or long winded rural bus journeys. All of which are totally worth it once you get there!

Dinner - good but restaurant menu broken, sounds picky but 5 star

Breakfast - For the price only offered 1 fried egg per person, buffet table did not have 5, 4 or 3 star options, extremely disappointing! Minimum low quality options, no fruit, yoghurt or the Std variations

Bar - when we got there was open but zero ambience, after dinner, library & roof top bar was accessible but dark, wasn’t sure if was open. Look as if not maintained, poor quality books, cupboards, fire place not lit. Completely unfair to paying customers. No lounge to go to after dinner, completely killed the mood

Spa - very good

Service - people were friendly

Overall experience of hotel was highly disappointing, we have been to many hotels in Spain & this one in particular has been the least value for money. I do not recommend at all, we drove 3,5hrs for a 5 star experience yet let with a daunting overly priced feeling of never visiting Rioja again!

Disappointed customer!

USB

UNDERSTANDING LA RIOJA

The Control Board monitors, audits, and controls the entire Rioja production process—from the vineyard to the market. For example, plantation density is restricted to a minimum of 2,850 vines and a maximum of 10,000 vines per hectare; that is a maximum production per hectare of 6,500 kg for red grapes, and a maximum production of 9,000 kg for white grapes. The Control Board also carries out frequent inspections to check stock volumes by wine type and vintage, the number of barrels and bottles, back labels, etc., to verify the information given by wineries. The origin, vintage and type of production of wines are guaranteed through secure back labels and seals, and quality control also extends to the marketing stage.

HISTORY OF THE CONTROL BOARD

La Rioja wines are protected by the oldest Designation of Origin in Spain. The modern Rioja was born in the late nineteenth century, establishing a clear link between the name of a product and the place where it was made. This sparked growing concerns among Rioja’s grape growers and winemakers, who needed to protect its identity against “usurpers and counterfeiters.” These concerns led to the official recognition of the Rioja Designation of Origin on June 6, 1925.

Since 1991, Rioja wines are protected by the first Calificada DO in Spain. Its Scope Statement establishes the borders of the production area, the grape varieties that may be grown, the maximum allowable yields, production and ageing techniques, etc. The Control Board is a public institution in charge of fostering and controlling wine quality, promoting the region and defending the interests of the region’s wine trade, whose representatives constitute the Control Board Management body.

Today, Rioja is one of the world’s Designations of Origin that offers the best guarantees regarding the quality and authenticity of its wines, and one of the few that require all of its wines to be bottled at source. Without a doubt, the Rioja Control Board’s effective enforcement of some of the strictest regulations among wine regions in the world offers the greatest assurance regarding the quality and authenticity of its wines, giving consumers security and trust—and which have been decisive in reaching Rioja’s leadership position in the market.

AREAS OF LA RIOJA

LA RIOJA ALTA

This area is on the right bank of the Ebro River. It has a continental climate with Atlantic influence, although the Sierra de Cantabria acts as a natural frontier to stop the passage of rain-bearing winds from the North. In this area, there are various types of soils, fundamentally calcareous clay, ferrous clay and alluvial soil.

Calcareous clay soils are rich in chalk, permeable and difficult to water and mechanize. It is a poor soil—precisely the type that is best for vines; therefore, they offer the best quality for the production of wine and are ideal for cultivating Tempranillo grapes. As a result, they make very stable wines, elegant and aromatic, perfect for ageing.

Ferrous clay soils, on the other hand, contain less chalk, although they are not easy to water or mechanize either. These soils produce fresher wines, with less body and more acidity.

Alluvial soils are permeable and rich in nutrients. They are permeable and easy to mechanize. It is said that they produce wines with good color.

LA RIOJA ALAVESA

The smallest region in terms of size and the most northerly. Therefore, the Atlantic has a greater influence on its climate: it is wetter and with lower temperatures than in the other two Riojan areas, both in summer and winter. The soils in which vines are cultivated here are calcareous and located on terraces or in small parcels.

LA RIOJA BAJA OR LA RIOJA ORIENTAL

The most easterly area, which makes the climate here drier and warmer, with more Mediterranean influence. The soils are predominantly alluvial and calcareous clay, and the plantations are greater in size and located at a lower altitude. This all ends up giving the wines greater structure and higher alcohol content than those in La Rioja Alavesa or La Rioja Alta.

VARIETIES

The image shows the number of varieties and their percentages in the 65,326 vineyard hectares in La Rioja.

This is the kingdom of the red Tempranillo and the white Viura grapes. However, the rest of varieties, specially the white ones, are clearing a path in the production of great wines.

CLASSIFICACIÓN

CLASSIFICATION ACCORDING TO AGEING

Crianza:

For red wines, the minimum oak barrel and bottle ageing period is two calendar years, from October 1st of that particular vintage year, followed and complemented by bottle ageing. The minimum barrel ageing period is one year.

In the case of white and rosé wines, the total period of time is the same as for reds, although the mandatory barrel ageing period is of six months.

Reserva:

For red wines, the minimum oak barrel and bottle ageing period is 36 months, with a minimum oak barrel ageing of 12 months.

In the case of whites and rosés, the total minimum oak barrel and bottle ageing period is 24 months, with a minimum oak barrel ageing of 6 months.

Gran Reserva:

The minimum barrel ageing period for red wines is 24 months, followed and complemented by a minimum bottle ageing of 36 months.

For whites and rosés: the minimum oak barrel and bottle ageing is at least 48 months, and the minimum oak barrel ageing is 6 months.

VINOS DE ZONA

Designation Regulations recognize the existence of three sub-areas or sub-zones since 1970: La Rioja Alavesa, La Rioja Alta and La Rioja Baja (now called La Rioja Oriental). Under the new 'zone’' designation, the Control Board has updated regulations and visibility of this indication on wine labels, which were implemented in 1998.

Requirements

1. Grapes must come exclusively from the zone.

2. Vinification, ageing and bottling within the zone.

EXCEPTION: Up to 15% from bordering municipalities in a different zone, and as long as long-standing ties with the vineyard dating back at least ten years can be proven.

VINOS DE MUNICIPIO

As in the case of Vino de Zona, the right to use the name of the town on the label has been recognized for almost 20 years. Specifically, since 1999. The new regulation will provide more visibility to this geographical indication.

Requirements:

1. Grapes must come exclusively from the municipality.

2. Vinification, ageing and bottling within the municipality.

EXCEPTION: Up to 15% from bordering municipalities, and as long as long-standing ties with the vineyard dating back at least ten years can be proven.

VIÑEDO SINGULAR

The new Viñedo Singular geographical indication designates wines from particular vineyards or estates. It is directly linked to the terroir, which it aims to identify and valorize on the label, in addition to the quality requirements that characterize excellent wines.

Requirements:

1. Grapes must come exclusively from plots within the Viñedo Singular.

2. Vinification, ageing, storage and bottling within the same winery.

3. Minor geographical unit that can comprise a single or several cadastral plots.

4. Minimum age of the vineyard: 35 years.

5. To prove—by means of any legally valid title—that it has exclusive use of the production of the Viñedo Singular for a minimum period of 10 uninterrupted years.

6. Maximum production: 5,000 kg/ha for red varieties and 6,922 kg/ha for white varieties.

7. Maximum grape-to-wine ratio: 65%.

8. Specific Grape Grower’s Card.

The traits that characterize Rioja Alavesa wine stem from the significant differences between this region and other wine-growing areas in terms of climate, soil, varieties, etc., even in the sophisticated care given to the vineyards and the unique vinification methods. Here are some of the special features of Rioja Alavesa viticulture.

Characteristics of Rioja Alavesa viticulture and oenology

This region is in an area of Atlantic-Mediterranean transition, which guarantees that most of the vineyards have enough amounts of sun and water. The southern orientation of that vineyard, settled down on the slopes of the Sierra de Cantabria, means that maximum use is made of the summer sun. These latitudes have a very high heliothermal index, together with the fact that 90% of the vineyard grows a grape as early as the Tempranillo—two key factors for an excellent ripening of grapes.

The region that has been known for centuries as "Rioja Alavesa" is a narrow piece of land about forty kilometers long and eight kilometers wide, located in the south of Álava, between the Sierra de Cantabria and the Ebro River.

It is about 40 kilometers south from Vitoria-Gasteiz, capital of the Historical Territory of Álava and the Basque Country, to which it belongs since the end of the Middle Ages.

The Rioja Alavesa covers around 316 square kilometers, barely ten per cent of the area of Álava, and it is inhabited approximately by 11,000 people, just over three per cent of Álava’s population.

There are 23 population centers in the region: Assa, Barriobusto, Baños de Ebro, Cripán, El Campillar, Elciego, Elvillar, Labastida, Labraza, Laguardia, Lanciego, Lapuebla de Labarca, Laserna, Leza, Moreda, Navaridas, Oyón, Páganos, Salinillas de Buradón, Samaniego, Villabuena de Álava, Viñaspre and Yécora.

It offers poor soils with great viticultural potential, such as the "calcium Cambisol" majorly present in the region. This means moderate average yields—between five thousand and six thousand kilos of grapes per hectare, another figure that points towards fruit quality.

Here we find very professional farmers, who have devoted themselves for centuries to this crop they know so well, and for which they annually invest large amounts of money in phytosanitary treatments and in the most careful cultivation techniques in terms of the quality of the bunches; with the latter resulting from the prevailing philosophy among our winegrowers of "caring for the vineyard as if it were a garden".

By analyzing some of these aspects, we can understand why the Rioja Alavesa is one of the world regions with the greatest viticulture vocation:

- Dry and sunny climate. Climate is a key factor that explains most of the differences between wines from different localities.

- Poor calcareous soil. The roots of the vine sink deep into the soil, exploring large volumes of soil to obtain the necessary nutrients. A powerful radicular system allows the vine stock to grow even in apparently very poor and dry soils.

- An exclusive vine. There is an environment-plant relationship that makes up the wine-growing ecosystem—and the latter factor is very significant. Each variety of Vitis vinifera has different light and heat requirements to complete its cycle and achieve the complete ripening of its grapes. Thus, in a specific habitat, less demanding vines will develop and mature earlier.

- Quality vinification: Tradition and technology. Wine continues to be like in the past—the son of the Earth and Sun. However, nobody doubts today that a good wine needs the help of man who, with his abilities and techniques, raises this product to the category of a masterpiece.

Remarkable differences:

Soil: Vineyard orientation, gradient, permeability, altitude, location.

Climate: Temperature, solar irradiance W/m2, rainfall, climatic events, hail, ice, wind

Plant: Age, variety, grafted rootstock.

Vineyard Culture: Training system, growing operations, vegetation management, plant health

Oenological Culture: Plant health, Ripeness, Grape harvest

MASSAL SELECTION

The traditional method of vineyard propagation to grow new vineyards or to rectify faults has always been the result of observation and experience. Phenotype—that is, the genetic inheritance of each organism, where all its physical traits are defined, such as height, bunch size, skin thickness, disease resistance, ripening cycle, etc.—always took precedence. As a result of the different harvests carried out over the years, wine growers were able to recognize what plants adapted best to the ground, which ones were more productive or suffered less from diseases, or in the best case scenario, which ones produced better wines. The so-called massal selection fell into disuse after the arrival of the phylloxera plague, although there are wineries that continue to collect plant material from their best vine stocks.CLONAL SELECTION

Clonal reproduction is agamic—a reproduction where the reproductive cells have no function and the wine grower’s work is aimed at obtaining the same exact plants, without any variability. The usual procedure consists of determining which vine stocks fit best our agro-technical or oenological requirements in order to clone them without limits based on a genetic health study. Working with certified clones reassures us and ensures that the behavior of each vine stock will be identical.

TEMPRANILLO

Thought to be native to La Rioja, it is the most characteristic variety of this Denomination—basis of the identity of its red wines and one of the world's greatest noble varieties. It covers more than 75% of the cultivation area and it is oenologically very versatile, capable of producing wines with long ageing; very balanced in alcohol content, color and acidity; and with a clear, soft and fruity taste, which evolves into velvet-like when ageing. With regard to its agronomic behavior, it is very safe to set, very sensitive to pests and diseases, not very resistant to drought and high temperatures and, as its Spanish name suggests, it is an "early grape" with a short ripening cycle.

GRACIANO

Graciano is a native variety that is not very widespread in other areas. Its complementarity ageing with Tempranillo grapes made it a future variety for La Rioja. Its cultivation area has considerably increased in recent years, although it has not reached the importance it had before the Phylloxera plague. It needs calcareous clay soils with a certain degree of freshness and is resistant to diseases such as downy mildew and powdery mildew. It has low fertility and late ripening. It produces wines with high acidity and significant polyphenolic content, ideal for ageing, with a very peculiar aroma and greater intensity than other varieties of La Rioja

VIURA

Best known variety in La Rioja. The great classic wines have been produced with this variety. It is chosen for its character and versatility. It produces wines with very good acidity and a high capacity of ageing. Great minerality. Ageing in barrels strengthens all its virtues.

Young white wines made with Viura are fresh, floral and aromatic as long as grapes are harvested early and ageing takes place in stainless steel. They can gain body and notes of honey and nuts once they have aged in barrels and if they have been harvested when grapes are more ripe. These Viura wines, aged in wood, are the traditional production of the classic white wines with barrels of La Rioja.

RIOJA SOILS

The soil where the vine is planted is one of the vectors of quality of the wines produced by that vineyard. In our Rioja Denomination of Origin, soils are classified into three main groups: calcareous clay soils, ferrous clay soils and alluvial soils. It can be said that calcareous clay soils favor wines with "body" and a perception of a higher volume in the mouth. Ferrous clay soils (red soils) produce medium-bodied wines, while alluvial soils produce light-bodied wines.

ELCIEGO SOILS

Our winery and vineyards are located in the so-called Rioja Alavesa. Out of the three Rioja areas, this is the one with more special features. The region has a barely modified landscape thanks to the abrupt topography, typical from Somontano and Sonsierra—with a southern orientation and located at the mountain’s feet. Unlike other wine-growing areas, the Rioja Alavesa is one of the few main vineyards in the world that is mostly located in small plots, both because of its particular orography and because it does not have the massive plot concentration seen in other regions.

Bodegas Fos’ vineyards are located in the Rioja Alavesa region, between 400 and 700 meters above sea level. Our vineyards have an almost absolute predominance of calcareous clay soils (brown soils) and basic pH. These soils developed on Neogene and Miocene marls and clays due to colluvial (mainly from the mountains) and alluvial formation. Some developed on sandstone plains and are shallow, flat, stony, limy, and loamy textured. Others are located on slopes, developed on marls; these are moderately deep, with slight slopes and few stones, calcareous and fine loam textured.

Calcisol, Cambisol and Fluvisol

According to the international soil classification, we have:

Haplic calcisol (calcisol = calcareous). Profile type ABC. The surface horizon is pale and ochric; the B horizon is cambic or argic, and may even present vertic properties. There is always an accumulation of carbonates in the C horizon.

There are also calcareous cambisols, characterized by a calcareous content over 25%, very poor in organic matter, with little accumulation of clay in the B and lower horizons, and under which there is a marly rock that allows easy penetration of the roots. It is yellow in color. These soils are well drained and very suitable for vineyard growing but not very fertile.

Profile type ABC. The B horizon is characterized by a weak to moderate alteration of the original material; and by the absence of significant quantities of clay, organic matter and iron and aluminum compounds. It is an illuvial horizon. There are also some small dotted spots in the ferrous clay soils’ area (petric calcisols or calcareous regosols) that are formed on sandstones, limonites, clays and marls. They contain less than 25% of limestone and a high proportion of clays, resulting in reddish-colored soils—usually with an excess of aluminum in their composition.

Alluvial soils (fluvisols) are also present in our area (terraces formed by the Ebro River). These are the most fertile and the most suitable for light wines. They are especially good for horticulture, as their flatness favors the accumulation of soil moisture.

The term fluvisol derives from the Latin word "fluvius" (river), referring to the fact that these soils are found on top of alluvial deposits. The original material is made up of deposits—predominantly recent ones—of fluvial, lacustrine, or marine origins. The profile type is AC, with clear stratification that makes it difficult to differentiate the horizons, although a very notable Ah horizon is commonly found. Redoxorphic traits are common, especially in the lower part of the profile.

CALCAREOUS SOIL - CALCIUM

Much is said about the ideal habitat for a vine. It is well known that calcium greatly influences the use of other nutrients, so its functions are directly related to the grape quality and the wine obtained. Calcium has a significant influence on the plant’s health, both in the root system and in the aerial part, and it is related to the formation of the rhizosphere and the microbiota of the soil.

In addition, it defines the soil’s structure and its capacity to supply water to the plant—especially at veraison, the moment of greatest water consumption. It is the only way to eliminate clays, by helping to combat toxicity due to aluminum excess in the soil. It is the only element capable of eliminating excess sodium from the root bulb

It is crucial for meristem growth and for the growth and proper functioning of radical apexes. It is a middle layer component, with a cementitious function as a calcium pectate. It prevents cell membrane damages by preventing the escape of intracellular substances. It seems to act by modulating the action of plant hormones, regulating germination, growth and ageing.

The submountain plateau where Fos vineyards are located has a marked inland Mediterranean nature: a temperate climate where winters are cold and summers are hot and dry, and where the average rainfall does not exceed 400mm per year—reaching its maximum during spring—, mainly due to the Foehn effect caused by the Sierra de Cantabria, north of Elciego, which limits the wet and cold influence of the Cantabrian Sea.

Temperature and water availability are the most important climate elements for the vineyard's development.

A prolonged period of mild temperatures is required to achieve ripeness.

The metabolic development of the vineyard begins with temperatures above 10°C and carries out its cycle of photosynthesis with average temperatures between 15° and 30°C. A significant difference in temperature between summer and winter allows the vineyard to enter a state of rest. The plant stops the ripening process with temperatures above 35°, while winter frosts below -15° may kill it. Temperature variations between day and night (thermal amplitude) also significantly affect how grapes ripen. If there is little variation, grapes will lack acidity; while if the difference is significant, grapes will be better balanced and will retain acidity.

It should be noted that every 100 meters above sea level the average temperature is reduced by approximately 0.6°C, and that planting on a hill with a certain orientation reduces vineyards’ sun exposure (sunshine is another key element, since it is the driving force of photosynthesis).

The orientation of both the vineyard and the vine rows, as well as the distance among them, the different pruning systems and the leaf mass treatment to increase or reduce exposure and aeration of bunches, are key elements aimed at optimizing the sunlight effects. These decisions will depend on the varieties planted, as each variety has different vigor and growth patterns.

The most relevant aspect of vineyard rainfall is not the volume of the rainfall itself but the moment of the growth cycle when it takes places, as there are wine-growing areas with very high or very low rainfall. Winter rainfall helps create water storage; rainfalls at the beginning of the growth cycle can affect the harvest size, while rainfalls before harvest can influence quality by diluting sugars and acids, as well as breaking the aromatic balance of the grapes. The most feared consequence of rain is the risk of fungal diseases that can quickly spread through the vineyard and ruin the harvest.

In some areas, there are always autumn rains. The only uncertainty is when will it rain. Every year, winegrowers have to take the risk of deciding between obtaining greater ripeness or having their harvest ruined by rain. Grapes grown in colder climate vineyards and with longer ripeness periods have more complex and interesting aromas, and that will be transferred to the wines.