Museo del Prado - Velázquez and 'Las Meninas'

last update: 20 Nov. 2019

In early May 2019 we were again in Madrid, and that meant again a visit to Museo del Prado. During our first visit in 2017 we focussed on the rooms containing altarpieces. This time we decided to focus on Diego Velázquez (1599-1660) and in particular on Las Meninas. In part this was inspired by our hotel which had used Las Meninas as one of the decorative themes throughout the public spaces and the bedrooms.

This webpage will look at who was Diego Velázquez and in particular we will look at one of his paintings Las Meninas. At the end of this webpage there are some links to video material that could be reviewed before or after visiting the content below.

Who was Diego Velázquez?

Diego Rodríguez de Silva y Velázquez was born in Seville, Spain, on June 6, 1599. His parents, Juan Rodríguez de Silva and Jerónima Velázquez, lived in Gorgoja, a tiny street in the neighbourhood of Santa Cruz. His father was of Portuguese origin and his mother and maternal grandparents were from Seville, which is why he was called 'El Sevillano'. Diego chose to be known by his mothers name, but we know little about his family, and no portrays of them have survived.

From the age of 9 to 11, Velázquez followed the painter Francisco de Herrera 'El Viejo' (1576-1656), who was in charge of his education. From the age of 11 (in 1610) Velázquez entered the house of the painter Francisco Pacheco del Rio (1564-1644) as his apprentice. He married Juana Pacheco, the daughter of his teacher, in 1618 (see portrait below).

He left for Madrid in 1622, and in 1623 Felipe IV (1605-1665) commissioned from him a portrait, which Velázquez completed in one day. In 1624 the King gave Velázquez 300 ducats to move his family to Madrid and become 'pintor del Rey'. In 1628 Velázquez would become 'pintor de cámara', the principle court painter holding the exclusive right to paint the portraits of the King. In 1629 Felipe IV sponsor Velázquez to visit Italy for 18 months. He would again visit Italy in 1649, but this time he would buy on behalf of the King paintings by Titian, Tintoretto, and Veronese. He returned to Madrid in 1651. He would paint Las Meninas in 1656, and 4 years later he would die in 1660.

Velázquez is considered to have developed his own unique style and palette, but it is also true that his colour palette did evolve as he travelled. When Velázquez moved to Madrid his compositions became more studied, highlighting the person portrayed against a lighter background. He started to use pink and lead white pigments, leaving aside the ochre tones (a colour often called 'tierra de Sevilla'). In 1627 he increasingly focussed on the themes of history and realism, adapting mythology to everyday scenes. In 1629 he made his first trip to Italy where he was presented as a portraitist. His brushstrokes became more fluid. After 1631 Velázquez's portraits took on a brighter silver tone, and his figures started to occupy the middle of the canvas. From 1636 the fluidity of his brushstrokes improved, and from 1643 his palette gained in depth and pictorial effects, making his painting much more 'impressionistic'. In 1649 he made his second trip to Italy. From 1651 to 1660 it was his final period, where his brushstrokes became even stronger and more determined, and he increasingly used pink and ivory tones.

It was in this last period that Velázquez would paint Las Meninas. As such his technique was at its freest and most fluid. We can see his palette contained pink or red colours with which he manages to capture the viewers attention and focus it on key areas in his compositions. For example, the ivory colours in dresses are made with large, loose brushstrokes that anticipated impressionism.

One element often ignored was that Velázquez was enrolled in the best workshop in Seville where he not only learned technique, but also the need, following the model of Italian academics, to study his topic as an essential compliment to the work of an artisan. It is often suggested that his meteoric career as a painter at the Court was due to his ability to find new ways to interpret classical themes. We also tend to forget that alongside his painting he was nominated in 1643 the Ayudante de la Superintendencia de Obras Reales (Assistant to the Superintendency of Royal Works), in 1647 Inspector de las Obras del Alcázar (Inspector of the Works of the Alcázar), and 1652 Superintendente de Obras Particulares. As such he was a kind of artistic director, responsible for the architectural and decorative reforms of the royal buildings (Alcázar de Madrid, Monasterio de El Escorial, Palacio del Buen Retiro, …).

Velázquez's working style

Velázquez had a very slow and meditative way of working, including moments of relaxation before the completion of a work. This was all on top of a meticulous preparation. The inclusion of periods of speculative reflection no doubt led to the introduction of changes. The changes are called 'pentimenti' and could be made at almost any time in the life of a painting. Velázquez was perfectly able to make changes some time later, once he had mastered a new technique. Also he was known to enlarge paintings, however it is often not easy to know who actually made the changes. These modifications pose a problem during restoration. Why were the additions made? Who made them? Are they original? Experts are certain that a number of Velázquez's paintings were modified later in life. But we also know that Velázquez was perfectly able to change pigments, resins, oils, as well as style, process and even conception, all within the same painting. The key, oddly enough, is that almost always when Velázquez made modifications to his paintings, he also changed their size. Almost as if the two changes were dependent upon each other. The real challenge for a restorer is to understand which modifications and changes were made by Velázquez and his workshop, and which were made later. Unfortunately we do not have any preparatory drawings from Velázquez, but they certainly existed. Also the sketching on the canvas was both methodical and at times quite 'loose', and changes and corrections (pentimenti) were for Velázquez all steps towards the final composition.

Art experts look at Velázquez's canvases as examples of perfect order. Everything still and in the right place, like a puzzle of colours, lights and shadows, all making sense. Yet Velázquez did not paint the truth, his deep knowledge of the trade allowed him to construct a kind of pictorial truth, or what some have called a 'transcended reality'.

One of the biggest problems facing an art historian is that with Velázquez there is an almost total lack of documentation (letters, biographical notes, drawings, etc.) that might help understand his intentions in one or other painting. Answers can only be found in his paintings themselves.

Las Meninas

Carl Justi, the German art historian, once said: "There is no picture that makes us forget this one", and he is right. Once you have seen in real life this painting, there is no other painting of the same type with which you can make a comparison.

The information provided by the Museo del Prado is an excellent starting point in describing what we see, and I will use it below.

So this is one of the largest paintings of Velázquez, and it's among those in which he made most effort to create a complex composition that would convey a sense of life and reality while "enclosing a dense network of meanings".

Wikipedia lists the works by Diego Velázquez, and they mention 143 paintings and 6 drawings, including some 36 'debatable attributions'. Las Meninas measures 318 cm by 276 cm, and only his equestrian portraits are larger.

From Antonio Palomino, who wrote a history of Spanish painters of 1724, we know that Las Meninas was painted in 1656 in the Cuarto Bajo del Príncipe in the Alcázar in Madrid, which is the room seen in the work. Palomino also identified the court servants grouped around the Infanta Margarita (1651-1673). She is attended by two of the Queen's meninas or maids-of-honour, María Agustina Sarmiento on the left and Isabel de Velasco on the right. In addition to that group, we also see the artist himself working on a large canvas. Then there are the dwarves Mari Bárbola and Nicolasito Pertusato, the latter provoking a mastiff. Further back we can see the lady-in-waiting Marcela de Ulloa next to the guardadamas Diego Ruiz de Azcona (attendant to the Queen). The chamberlain of the Queen, José Nieto, stands in the doorway in the background. Reflected in the mirror we see the faces of Philip IV (1605-1665) and Mariana of Austria (1634-1696), the Infanta's parents, who are watching the scene taking place. We know from Palomino that the King, Queen and courtiers would frequently visit Velázquez's studio to watch work in progress.

When the painting was produced the Infanta was 5 years old. Isabel de Velasco is said to have been 20 years old at the time. She had been the 'menina' to the first wife of Felipe IV, however she would die 3 year after the completion of Las Meninas. María Agustina Sarmiento is also said to have been 20 years old at the time and some reports say that she was the 'menina' of the Infanta and some say she was the 'menina' of the Queen. Little is know of the dwarf Mari Bárbola, however despite being mocked by the Court, here she stands upright and dignified. It is thought she might be about 30 year old at the time Las Meninas was painted. Nicolasito Pertusato came from a noble Italian family and was 21 years old at the time the portrait was painted. He was not treated as a Court buffoon, and is said to have had some understanding of medicine. Marcela de Ulloa is thought to have been about 30 year old at the time Las Meninas was painted. Diego Ruiz de Azcona was the son of a noble family and was about 35 year old at that time. José Nieto was about 40 year old at the time Las Meninas was painted.

Las Meninas was painted in the same room as shown in the painting itself, i.e. the 'Galeria de Mediodía' in a part of the Real Alcázar de Madrid called the 'Cuarto del Rey' (the King's quarters).

The Alcázar had grown in importance in the 14th C and 15th C in part because it housed, with Segovia, the royal treasury. But it was unpleasant as a residence, being dark, cold and uncomfortable. The walls were thick as befitted a fortress and windows were few and narrow. It was said that this was to avoid the sun, but reports suggest that it more likely due to the cost of glass. Even as late as 1691 many windows in the Alcázar were shuttered, but without glass in the frames. It was in 1537 that Carlos V (1500-1558) decided to modernise and extend the building in the Renaissance fashion. However it would be Felipe II (1527-1598) that would create a model of palace architecture that would persist through much of the 18th C.

The starting point would be the Torre Dorada in the south-west corner, which was built in the so-called 'estilo de Los Austrias' (the Austrias style, and a style later adopted for El Escorial). Felipe II moved the Spanish capital to Madrid in 1561, and the Alcázar became the royal residence (his quarters were in the south-west wing).

The style of the Torre Dorada was copied throughout the city, reinforcing the presence of the monarchy beyond the palace. Again it was Felipe II who ordered the interior decoration in the Italian style. Because Felipe II placed his office in the tower, it also became known as the Torre del Despacho.

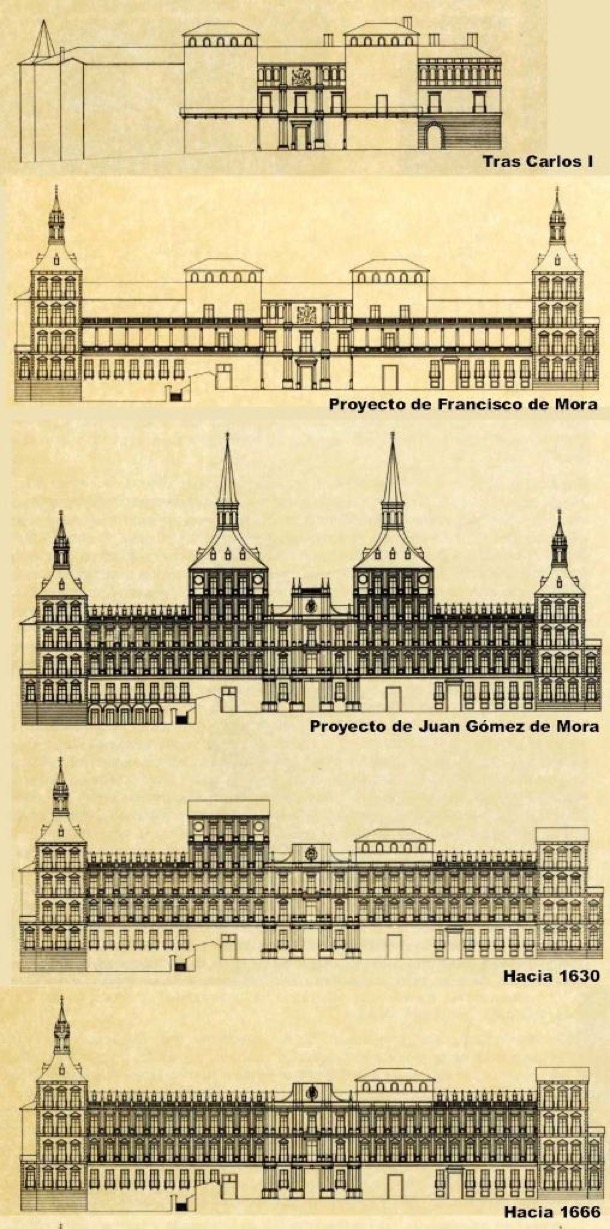

Felipe III (1578-1621) would remodel the main façade and add the Torre de la Reina in a similar style. Juan Gómez de Mora (1586-1648) would start the work, but would later be replaced by Giovanni Battista Crescenzi (1577-1635) for 'delitos monetarios'. Crescenzo would remove the two towers on the front and create a new façade with a new entrance and large regular balconies. Spires would be added to the other corner towers.

Our Felipe IV (1605-1665) would initially follow the building of the Palacio del Buen Retiro, but in 1639 he would return to the Alcázar.

There he would order the complete renovation of almost all the rooms, and the creation of a room called Ochavada (an eight-sided room). He would add connecting stairs to the different floors, and would order on the floor above the office, the building of his personal library (by 1637 it would house 2,234 volumes). It would then be the turn of Velázquez to transform the interior of the Alcázar into a unique palatial space.

Later, the fire of 1734 would give Felipe V the opportunity to build a new palace more to his taste.

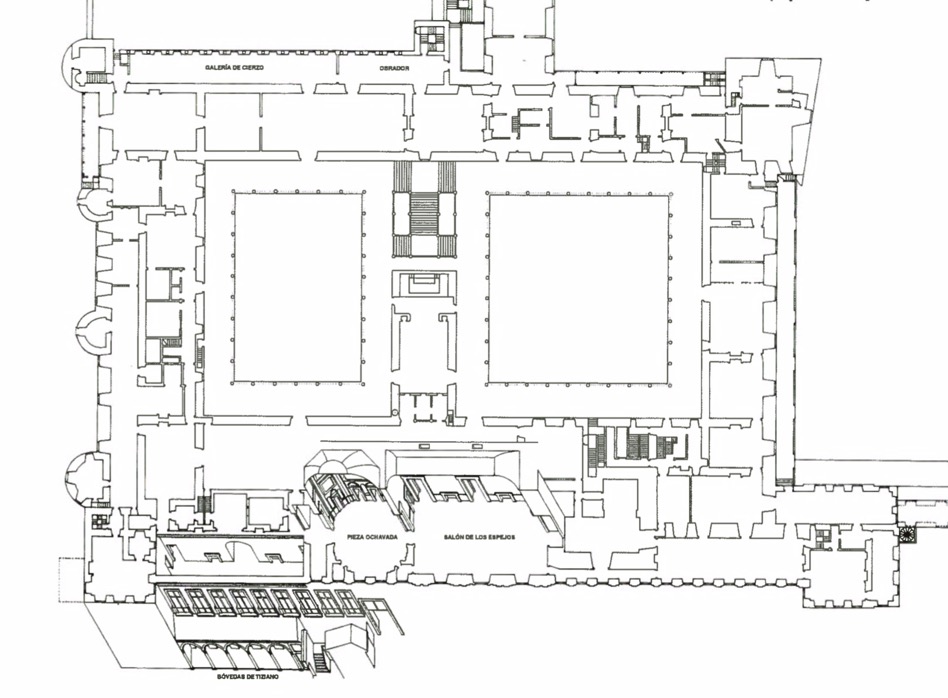

So the 'Cuarto del Rey' was where "duerme el Rey, escribe, firma y despacha" (where Felipe IV sleeps, writes, and signs dispatches). The 'Galeria de Mediodía', overlooked a garden adorned with fountains and statues of Roman emperors. Being on the south side it was pleasantly warm also in winter time, and Felipe IV liked spending time there when the weather was bad. As best as can be understood the 'Galeria' was grouped together with the 'Pasillo del Mediodia', the 'Ochavada' and the 'gabinete del salón de los espejos'.

As we have already written, the centre of all attention in Las Meninas is the Infanta Margarita (1651-1673). However, the first wife of Felipe IV, Isabel de Borbón (1602-1644), had 10 pregnancies throughout her life. Four were premature births and four time she gave birth to weak children who died shortly after birth. Of all of them, only Baltasar Carlos (1629-1646) and the Infanta María (1638-1683), future wife of Louis XIV of France, reached puberty. Baltasar Carlos did fall ill at the age of five, but recovered. In 1644 he was promised to his first cousin Mariana of Austria (1634-1696), and that same year his mother Isabel would die in childbirth. Upon the premature death of Baltasar Carlos, Mariana would finally become the second wife of his farther Felipe IV, who was 30 years older than her. Baltasar Carlos would again fall ill in 1646 whilst visiting Pamplona with his farther, but he again recovered and went on to Zaragoza. There, it is said, his tutor provided him with a "mujer de encantos arrebatadores" (a woman of captivating charms), who probably infected him with a serious illness. Baltasar Carlos was diagnosed with smallpox, and he died on the 9 October, 1646.

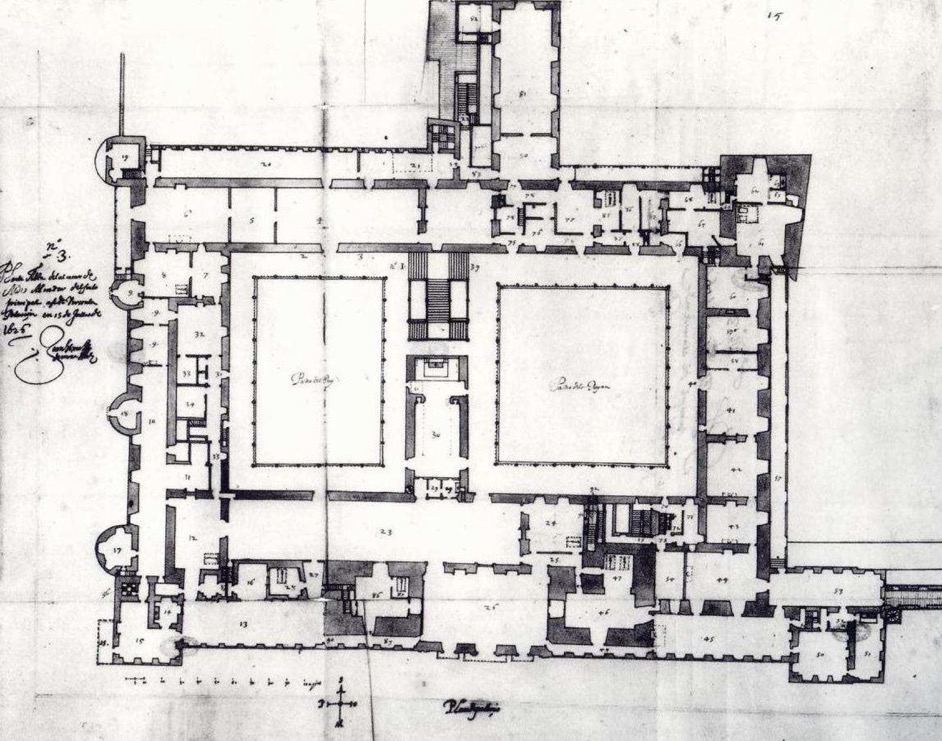

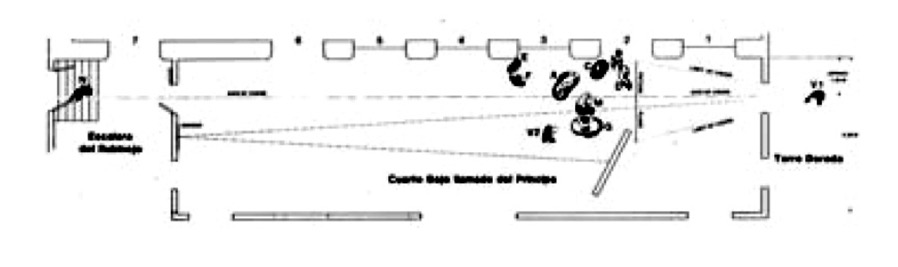

It is my understanding that Baltasar Carlos also lived in the 'Cuarto del Rey' along with Felipe IV, and the 'Galeria de Mediodía' was renamed the 'Cuarto Bajo del Principe'. We often see the 'planta principal' presented on the web, but above we have the so-called 'planta baja' dating to 1626, and we can just see the 'Galeria de Mediodía' right in the bottom left-hand corner (number 13). Below we have the 'planta principal' dating from 1665. We can see the 'Galeria de Mediodía' is fronted by the 'Bóvedes de Tiziano', a vaulted open gallery. It was in the rooms collectively known as the halls of the 'Bóvedes de Tiziano' that some of the earlier 'poesie' of Titian were hung.

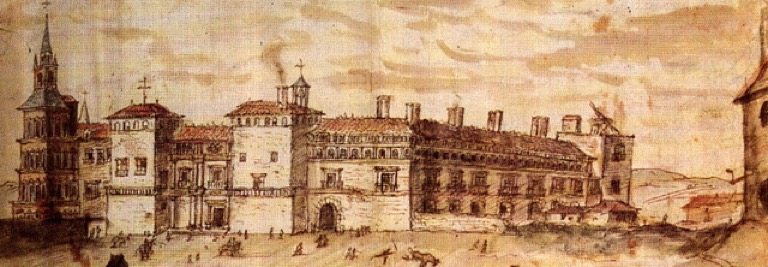

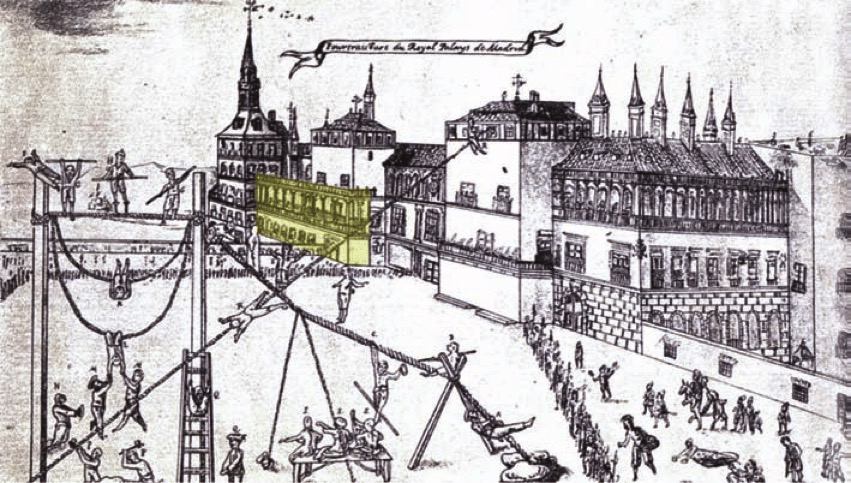

This terrace would disappear into the façade when it was remodelled. Below we can see the façade of the Alcázar dating from 1596-97, and marked in yellow we have the 'Galeria de Mediodía' and the covered upper terrace (which I think might have been called the 'Pasillo del Mediodia').

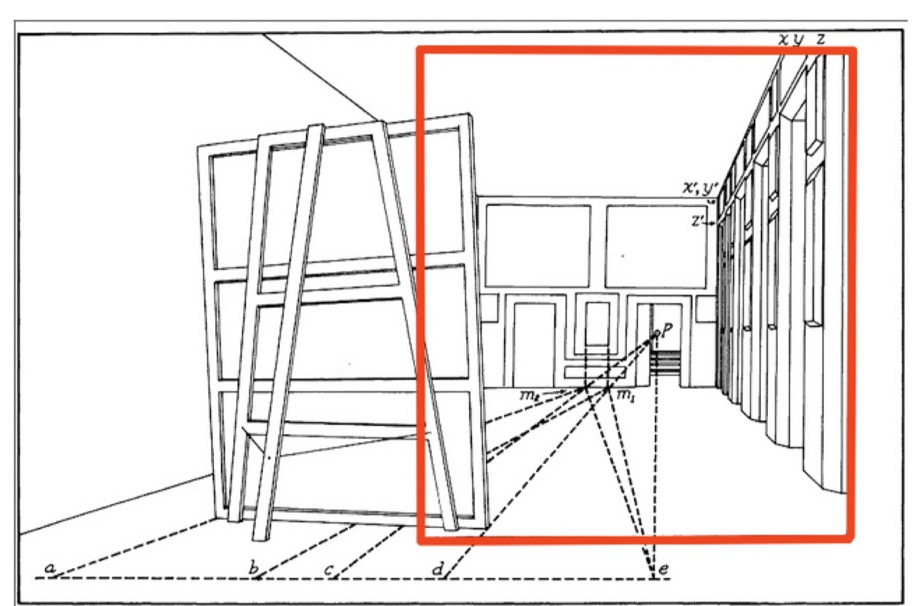

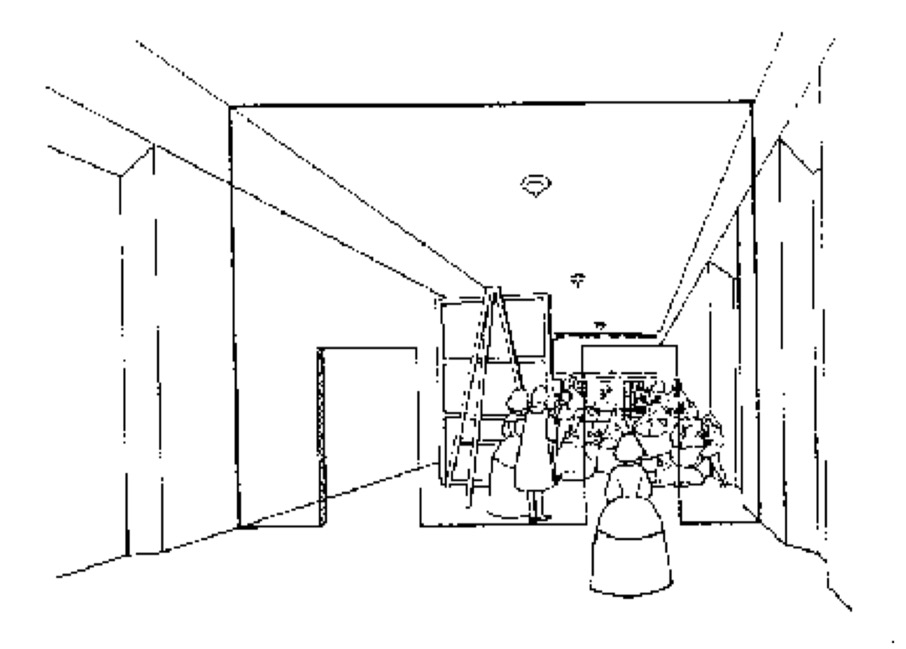

Upon the death of Baltasar Carlos the 'Galeria' would become the workshop of Velázquez. Below we have a reconstruction of the three key rooms, the 'Galeria de Mediodía', the 'Ochavada' and the 'gabinete del salón de los espejos'. This is taken from the article of Antonio Sáseta Velázquez.

The excellent article by Luigi Cocchiarella described fully the physical situation in which Las Meninas was painted.

There are a number of websites dedicate to the history of the period, notable are Pasión por Madrid, Investigart, a webpage on 'Historias del Alcázar de Madrid', and the website of the Asociación Española de Amigos de los Castillos is always worth visiting.

Just as a passing detail, today we might find it odd that rooms are all linked together and corridors (a favourite with modern architects) are not used. This was because at the time it was considered a bad omen to leave a room through the same door that was used to enter a room. Also protocol was strict in determining who could, and who could not, go from one room to another, getting ever closer to the sanctuary of the King's bedroom.

Las Meninas did not receive universal praise, particular from some of the other painters practicing in Madrid. Angelo Nardi (1584-1664), also a Court painter, accused Velázquez of not respecting the Infanta by placing her as an equal to dwarves and dogs. He was also accused of not giving a prominent place to the King. It would appear that other Court painters were antagonistic towards Velázquez throughout his time at the Court, to a point that even after his death they spoke ill of him and asked for an immediate inventory of his assets. Nor did the other Court painters like the fact that Velázquez was allowed to have his workshop in the palacio, and that the King would occasionally 'pop-in' to see progress.

The museum website provides a first analysis. Las Meninas has one meaning that is immediately obvious to any viewer, it is a group portrait set in a specific location and peopled with identifiable figures undertaking comprehensible actions. The paintings aesthetic values are also evident, in that the setting is one of the most credible spaces depicted in western art. The composition is said to combine unity and variety, and the remarkably beautiful details are divided across the entire pictorial surface. Finally, it is claimed that the painter took a decisive step forward on the path to illusionism, which was one of the goals of European painting in the early modern age (i.e. puts the viewer inside the physical space on the canvas). This meant that Velázquez had gone beyond transmitting resemblance in order to successfully achieve the representation of life or animation.

However, as is habitual with Velázquez, in this scene in which the Infanta and the court servants pause in their actions on the arrival of the King and Queen, there are numerous underlying meanings. This painting has been the subject of a vast number of interpretations. An alternative is that Velázquez is painting a portrait of the King and Queen when, without notice, they decide to leave. Partusato might be just gently awakening the King's mastiff, and Nieto is simply preparing the way for the Queen. If this is true the portrait on which Velázquez works has been lost, and was never inventoried. As far as I understand things the mirror is the only 'portrait' in existence of the royal couple together.

You can look at the painting as a simple painting, or as a kind of photograph representing a moment in time, or you can look at it as being full of messages or 'signs' that need to be deciphered. Was Velázquez just trying to capture a sensation of surprise upon the unexpected arrival of the King and Queen, or was he planning something more?

The title Las Meninas refers to the ladies-in-waiting, but some experts still consider it a portrait of the Infanta Margarita. Others might even consider it a self-portrait of Diego Velázquez himself.

An alternative view of Las Meninas, can be quite prosaic. A little girl is being offered a drink, but she is not interested. A dwarf tries to tease a dog. A woman is talking to a man who looks bored. Someone is leaving, seeing little to detain him. The windows are shuttered, and the paintings on the walls are almost invisible. We can't even see what is on the canvas, and the painter looks hesitant. No wonder some of the characters are looking at us, probably hoping we will do something to break the monotony. But if the painter is trying to capture what he sees in front of him, then not only are the two people seen in the mirror in the painting, but so are we. I am seeing myself being seen.

Yet another view is that the mirror on the back wall, in which we see the King and Queen, is in fact just an old and very faded picture of the royal couple. Another suggestion is that the mirror is simply reflecting the image of a painting of the royal couple hanging on the unseen fourth wall. Does that mean that we are the sole subject of Velázquez's efforts? I think not, because as one expert noted Isabel de Velasco, the 'menina' on the right, is the first person to have seen the arrival of the royal couple and she has started on her curtsy or sign of reverence. Just maybe, the guardadamas Diego Ruiz de Azcona might also be showing surprise at the arrival of the royal couple. And even the hesitation in the hand of Velázquez could also be due to his surprise at the unexpected arrival of the royal couple. If, as suggested, we are seeing a surprise visit of the royal couple, then the mirror becomes the protagonist of the entire painting.

Yet another option is suggested by the fact that the vanishing point is very near José Nieto standing in the doorway at the back of the room. This suggests that the viewer (you and me) along with the royal couple are standing at an angle to the mirror. The conclusion is that the mirror is reflecting part of the tall canvas on the left, i.e. Velázquez is in the process of painting a portrait of the royal couple.

So there are numerous ways we can look at Las Meninas, and I've used as a starting point a wonderfully rich article by Byron Ellsworth Hamann entitled "The Mirrors of Las Meninas: Cochineal, Silver, and Clay". This article is worth reading not just for the detailed analysis of the Las Meninas, but also for its in-depth look into the way Spain exploited the New World. The article is accompanied by a series of critiques on Hamann's article.

At the time we were standing in front of the Las Meninas in the museum it did not cross my mind that we were looking at a 'monstrosity'. This term has been used to describe paintings that have 'outgrown' the discipline of art history. Like the Sistine Chapel or the Mona Lisa, the scholarship surrounding Las Meninas is so vast that no single person can grasp it all.

There are experts who honestly suggest that Las Meninas might be "the greatest achievement in the history of painting". They recognise that the painting itself is exceptional and a singular work of the past, but they also see it as a living piece that still attracts artists to imagine new interpretations. It continues, after more than 350 years, to mesmerise both the public, the artist, and the historian. And it is ironic that despite the encyclopaedic knowledge we have of Las Meninas and the enormous number of different interpretations of the 'meaning' of the painting, no one is convinced that we understand the painting as a whole.

During a visit of Salvador Dalí and Jean Cocteau to the Prado, Dalí was asked which painting he would save if the museum was on fire? As was his habit Dalí answered in the third-person, "Dalí se llevaría nada menos que el aire, y específicamente el aire contenido en Las Meninas de Velázquez, que es el aire de mejor calidad que existe" (Dalí would take nothing less than the air, and specifically the air contained in Las Meninas de Velázquez, which is the best quality air that exists). Does this sound odd? Perhaps not! In the early days people through that the air was the way the soul of something reached out to the real world. The word 'chiaroscuro' was coined initially to describe the 'perspective of light', how to use light and dark and 'make an image look like an object and an object like an image'. A nice description is that Velázquez managed to make the frame of painting intersect a room whose roof, walls and floor extend out to include the spectator. Las Meninas is not designed for the eyes of the spectator, but for the spectator's body. I suppose the sense of Dalí's comment was that you don't just look at Las Meninas, but you stand within it, breathing in its air and feeling its spirit reaching out to you.

Velázquez's canvases

We tend to forget that through the 16th C paintings were made on wood, and it was the Venetian painters who developed and popularised the use of canvas. It was only in the 17th C that canvas would finally prevail. The Prado Museum has an interesting webpage on the use of canvas in Spain from the 16th C onwards. Today a canvas for painting is usually made from cotton fibres, however historically a canvas would have been made of a tightly woven hemp (the same basic material was used to make sails), and later linen was also used.

According to the article on the Prado website, wood panels and canvases both required some kind of basic preparation followed by a primer layer that would seal the absorbent surface and provide a base on which to build the painting. By Velázquez's time the techniques were well established. As far as I can see, initially canvas's would be first covered in a gypsum ground layer before being primed, however in the 17th C an oil-based primer layer was used without an underlying gypsum ground. It would appear that Velázquez initially used a primer of brown coloured earth pigments with a significant amount of calcium carbonate content and a small proportion of charcoal black and white lead. If a ground layer was applied, it would have been a very thin layer of animal glue or some light inert material. When Velázquez finally settled in Madrid in 1622 he substituted the brown priming layers with a red ochre based primer, commonly found in Madrid. The suggestion is that Velázquez simply obtained his materials from specialist workshops who prepared the canvases for painters. When Velázquez returned from his first trip to Italy in 1631 he changed his painting technique, a change he would maintain until the end of his life. He introduced a light-toned, whitish, greyish or pinkish priming layer based around white lead. A lighter primer certainly appeared justified for the outdoor scenes.

My understanding is that as canvas became popular, specialist shops would buy rolls of canvas from weavers and sell them to artists in different formats. The shop would prepare the canvas possibly with a base and then one or more coats of primer, creating a smooth surface on which to construct the painting. An artist could also buy full or partial rolls of raw canvas and their assistant would cut and mount individual pieces on a strainer and then apply the base and primers. Today experts are able to identify paintings using canvases from the same role, and this is one way to attribute different paintings to the same artist. Computer algorithms are used today to provide thread counts across the entire surface of a painting, and in both directions. From this weave maps can be created and used to compare two different paintings.

Another equally unusual feature of the work of Velázquez concerns the size of his canvases. As a royal painter he was certainly constrained by a rigid protocol concerning any portraits of the King or royal family. The church would also impose specific constraints on religious topics. If we look at the sizes of his canvases we find absurd dimensions such as 81.3 cm by 69.9 cm. This is because until ca. 1800 length was measured in the Castilian Rod (Vara Castellana). Also today it is difficult to know what the size of an original canvas was. Many paintings have been cut, adapted to different hanging spaces, or simply modified according to aesthetic tastes of the time. Also almost all have been re-backed and re-framed. When re-framed it is was not uncommon to fold the canvas edges and place the painting on a slightly smaller frame. In some cases canvases were enlarged, and other painters asked to extend a composition. These changes could also involve painting in or painting out particular features. It was quite common for identical copies to be made, and those copies today can be found in different museums spread around the world. The same painting, copied many times, can now be found to have quite different dimensions.

In the 17th C there was a regulated market for frames, controlled by the guild of carpenters. There were a number of different types of carpenters, e.g. those who worked with either white or dark woods, those who built constructions for civil works (scaffolding), quadristi (panel builders), wood turners, and portaventaneros (door and window makers). Then there were the entalladores (wood carvers), sambladores (furniture assemblers), or ebanistas (cabinetmakers) who usually only worked with rare and noble woods. The carpenters who made frames usually only worked with pine. The guild of carpenters controlled those who could draw, design, colour, lacquer, inlay, and carve fine woods, and they were controlled by the municipality and the local mayor. In Seville Velázquez bought his frames in the same way as any other artist, but in Madrid as the Kings painter he was able to order any frame of any size. It is true that the great masters had their workshops and apprentices to prepare the materials and pigments. But Velázquez had a master carpenter in the guild, Martín Gaxero, to do his bidding. There exist payment receipts of 1,100 reales for the dressing of canvases.

Already in Seville Velázquez had a preference for frames with certain ratios of length to height, ratios based upon a theory of proportions. A theory related to the concept of ideal architectural orders. And it has been said that by the end of the 16th C the concepts of musical harmonics had also been fully implanted in architectural practice. So we have Velázquez preferring the dimensions of frames that echoed the concept of ideal architectural constructions, which in themselves were imbued with 'harmonious' thought. This is a complex series of arguments, but one worth reading in the article of Mario Criado Pérez. As a justification of this line of thinking it was noted that of the 154 books that were in the Velázquez's personal library the vast majority were on architecture, including 5 different editions of the treatise of Vitruvius, De Architectura.

We have to remember that Velázquez was also the 'decorator' of some of the royal palaces and apartments. As such he was also responsible for hanging paintings by Tintoretto, Raphael, Andrea del Sarto, Titian, Correggio, Veronese, Van Dyck, … By the mid-1700's the proportions of architecture and paintings were more or less in agreement. However, it is certain that Velázquez will have enlarged or reduced the measurements of an unknown number of masterpieces in order to fit them into one or other palace, and in accordance with the tastes of the day. In reality this was not unusual, and as an example, it is well known that in 1715 Rembrandt's The Night Watch was trimmed on all four sides so it would fit between two columns.

Velázquez - perspective and technique

Perspective

One of the most important element in Las Meninas is the way Velázquez handled perspective. In art the ability to represent a three-dimensional space on a two-dimensional flat surface emerged during the Italian Renaissance. Artists such as Filippo Brunelleschi (1377-1446) and Paolo Uccello (1397-1475) studied linear perspective, and incorporated it into their artwork. The two most important features of linear perspective are that objects appear smaller the further away they are, and that objects are foreshortened, i.e. dimensions change along the line of sight but remain intact across the line of sight.

What the Baroque (1730's onward) did was introduce a sense of spatial depth. Not based only upon linear perspective, the feeling of space and depth are also created through the senses. This is through the graduation of line thicknesses, through the variations in lighting, and through nuances in colour. As an example, someone submerged in darkness gives the sense of moving away or moving back. Colours that are clear, luminous, rich and full of nuances are perceived as being nearer to the viewer. Figures and objects that are distant receive less light and are perceived as fuzzy or less sharp (and are more often backlit as with the figure of José Nieto standing in the doorway). There is a sense of openness in terms of composition and space in the foreground, trying to include the viewer as a protagonist in what is happening.

Many experts found that Las Meninas is a picture created not from the point of view of the artist, but from another spectator who also happens to be one of the subjects of the picture. In part this view was based upon the idea that the vanishing point was, or must be, the mirror. However it is actually located in the open doorway very near José Nieto. Others deduced that the refection in the mirror could not be the royal couple, and therefore it must originated from a central region of the canvas on which Velázquez was working. A refection that should also have included the back of Velázquez standing in front of the easel. The analyses of perspective has been performed a multitude of times, and with increasing accuracy. If we look carefully at the mirror we can see light leaking into the area in the lower right corner. Which according to some experts would be a refection from a blank canvas sitting in front of Velázquez.

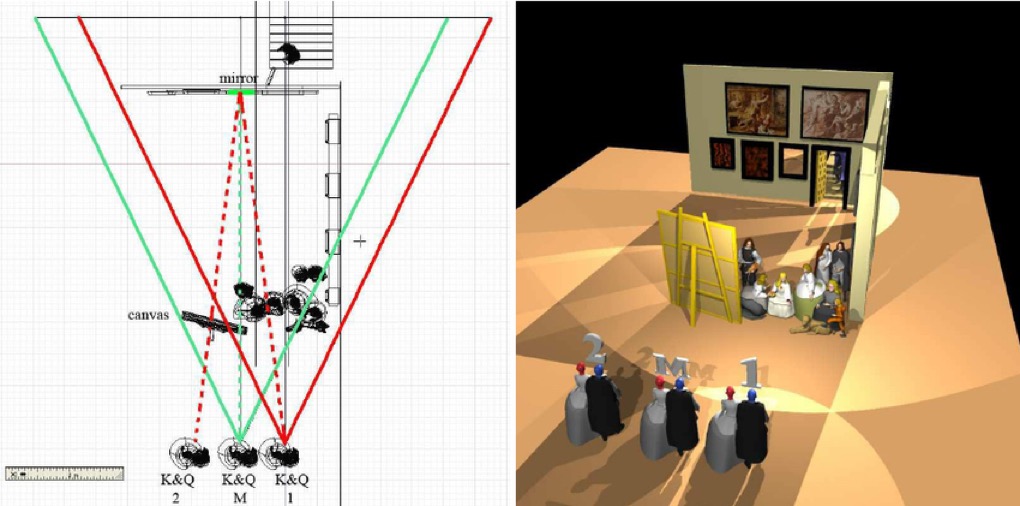

Above we have the analysis of Joel Snyder, who also sensibly suggested that it was a mistake to assume that the royal couple occupied the work's 'point of view', i.e. the painting 'must' represent the King and Queen's particular perspective. However if we simply assume that the viewer (or the painter himself) occupy that location, then the source of the refection in the mirror could be outside the picture or from the large canvas standing before the artist.

Neither of these possibilities should detract from the idea that the mirror 'proves' to us that the King and Queen were in the workshop.

In 1983 a certain John Moffitt reconstructed the room where Las Meninas was painted. The building was destroyed by fire in 1734, but the plans still exist. What he concluded was that the royal couple probably stood (others say they sat) directly opposite the work's vanishing point. And they probably stood just outside the main room, the suggestion is that their view was framed by an open doorway. This might explain the red curtain in the mirror, since it could be a door curtain pulled back to allow them to enter the main room.

Moffitt also found that the intention was to hang Las Meninas is the executive office of the King, a room immediate above the room where it was painted. This is quite compelling since the floor plan on the upper floor modelled that on the lower floor, meaning that the royal couple would enter the office of the King in the same way they were imagined to be entering the room in the painting. So the suggestion is that the painting was intended as a private painting for Felipe IV. Given that the King was the anticipated audience, all the questions of decorum concerning royal portraits went 'out of the window'.

My background tells me that perspective is a vital component is creating a space that is true to life, and therefore is more likely to convince the viewer to 'enter' the painting. Yet in this case, I have a lot of sympathy with the idea that a 'perfect' perspective is not essential to our understanding of this painting, nor does it affects our pleasure in viewing it hanging in the museum. Some of those experts who suggest that Velázquez used mirrors to create his masterpiece, also suggest that the painting is in fact a mix of images taken from the refection from several mirrors, and thus Las Meninas actually corresponds to a merging of several, slightly different perspectives, i.e. several points of view and several sources of illumination.

No matter what the study of perspective tells us, the royal presence is still the most plausible explanation for the outward glances of the characters. Ambiguities and 'puzzles' in a painting are not to be solved, but to be simply experienced and appreciated for what they are. And I quite like the idea that every time the King entered his summer office he would be 'interrupting' the figures in Las Meninas as it hung on the far wall.

Palette and pigments

The palette that the painter holds in his left hand gives us an idea of the colours and pigments he applied. Except for blue, it is a synthesis of his favourite pigments. Velázquez is known for having used a very small palette of colours throughout his life. What evolved with time was how he mixed and applied them. By the 1630's he had mastered the techniques, and what remained was to use and adapt them to each occasion. He was able to create a masterpiece using only five or six pigments. Painters would often grind and mix their colours in their own workshops, and then mix the pigments with protein binders (glues, animal fat, eggs), lacquers or oils. Velázquez would always use good quality pigments and specially purified and prepared oils. He always would pick and mix depending upon the translucence required.

It is the chemical analysis of the samples taken from the painting that tells us exactly the pigments used by Velázquez. In the case of Les Meninas the preparation of the canvas was made of lead white mixed with iron oxides (ocher), calcite and organic black, forming a white base. The colours have been obtained by adding the pigment corresponding to the desired colour in each area to the lead white, although in some areas the fine touches were made with almost pure pigments.

The chemical analysis detected these different pigments:

The yellow came from lead-tin (Pb2SnO4) or iron oxide (yellow ochre, or iron oxide hydrate, was used in the restoration)

The blue is azurite (copper carbonate) and the ultramarine blue was obtained from the lapis lazuli mineral

The brown came from the oxides of iron and manganese

The green came from a mixture of azurite and green pigments (lead and tin, iron oxide)

The black, known as carbon black, was an organic product of vegetable and animal origin

The reds came from mercury vermilion, red organic lacquer and red iron oxide.

The white, called 'lead white', was used constantly by Velázquez. He would mix it with calcite to increase the density of the mixture, or with flax oil (linseed oil) to make it less transparent. Lead white is an artificial pigment, used since antiquity and through until the beginning of the 19th C. It was obtained by reacting lead with an acid. One of the basic properties of pigments is that they must be chemically inert and not alter their colour with the passage of time. However lead white has the disadvantage that when used in an aqueous medium, over time it tends to darken (yellow). Also due to the effect of hydrogen sulphide (present in polluted air) lead turns to black lead sulphide. This effect of blackening does not occur in oil paints, because the oil components protect it from the effect of polluted air and moisture. As a carbonate it neutralises the fatty acids resulting from the decomposition of the oil, so it acts as a stabiliser making the pigment more flexible thus reducing the cracking caused by the passage of time. On the other hand, as oil paint ages, lead white loses its covering capacity by reacting chemically with linseed oil. The result is that it decreases its refractive index and becomes transparent, bringing out 'pentimenti', i.e. making visible what might be considered 'regrets' or what was originally designed or painted before the artist made changes to the original idea. Pentimenti can be seen in the left leg of Nicolás Pertusato and in the right hand of the Infanta (she originally was rejecting the offer of scented water).

Another drawback of lead white is its toxicity when inhaled as a powder. It damages the nervous system (lead poisoning) presenting symptoms such as headaches, colic, deafness and even can cause death. Painters, like Francisco de Goya, made their own colours and manipulated the pigments directly. So the risk of intoxication was high. It is possible that Goya, who preferred to grind his pigments with lead white, suffered from this disease. Some modern painters continue to use lead white for historical and aesthetic reasons. Pre-prepared pigments are not volatile at room temperature, so respiratory poisoning is very unlikely. However grinding the pigments as a powder can be dangerous. This problem can occur when removing lead paint in older houses, i.e. scraping or sanding. Currently, white lead has been replaced by another white pigment, titanium dioxide. This was used in the latest restoration of Las Meninas. It has the added advantage that it absorbs part of the ultraviolet radiation, thus protecting the surface of the painting.

Vermillion is the most famous bright red pigment used since the beginning of time. It is obtained naturally by pulverising cinnabar ore (mercury sulphide). With the vermilion, numerous colours of pink and orange can be obtained just through the grinding process. For example, the pink tone of Infanta Margarita's cheeks is achieved with cinnabar, lacquer and lead white. This pigment is darkened by the action of light. However, in oil painting, oils act as protective filters against the effect of light, so that the pigment remains unchanged.

As all mercury compounds are toxic and when entering the lungs through the blood, they can accumulate in the body, causing serious problems in the nervous system (neurotoxic). Many of the alchemists who used mercury ended up with serious health problems. Currently, it has been replaced by other pigments, such cadmium red (cadmium sulphide).

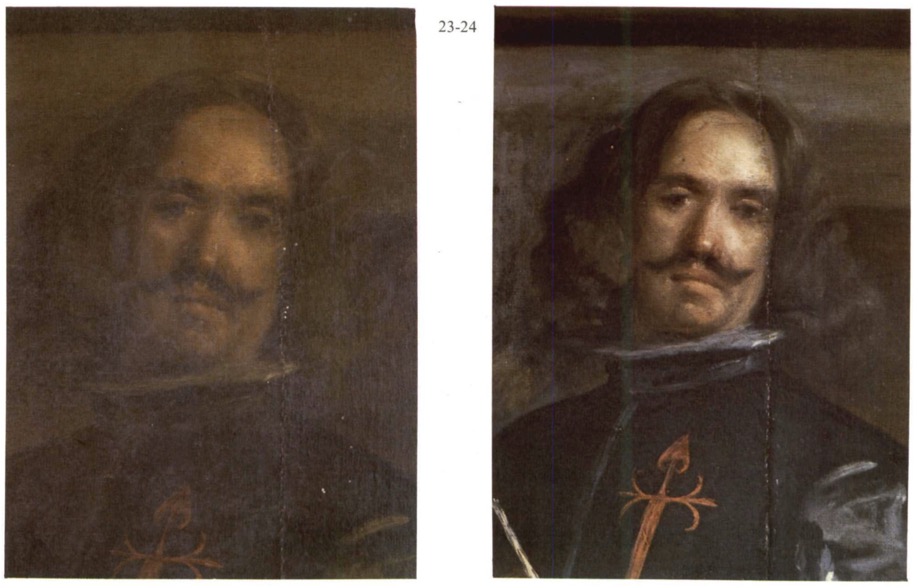

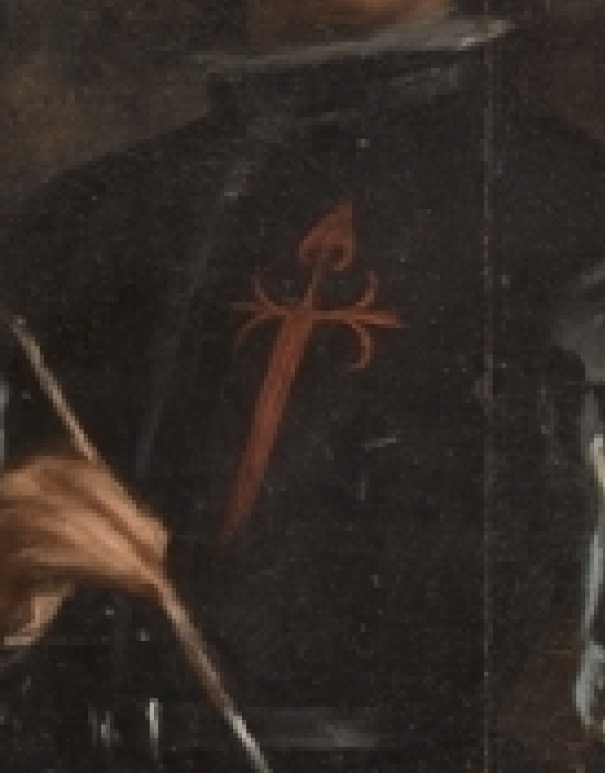

One of the great enigmas in the picture of Velázquez is to identify the author of the red cross of the Order of Santiago that appears painted on his chest. The cross of Santiago is a Cross of Gules (in heraldic terms this means intense red). The general design is one of a sword, with the hilt and its two arms finished in a fleur-de-lis. Soldier-Monks wore them on their cloaks, banners and chest. The cross of the order of Santiago was granted to Velázquez three years after Las Meninas was finished, and a year before Velázquez died. According to the biographer of his time, Antonio Palomino, the painter was dead when the King ordered that the cross of Santiago be painted on his chest. The great friendship that united the King with the painter, is evident in three words that the monarch wrote in a memorandum after his death: "I am shaken".

The idea that Felipe IV himself painted the cross of the Order of Santiago on the painter's chest in Las Meninas might be improbable. However, it might contain some truth, because there was a link between artistic nobility and social nobility. Velázquez wanted to be admitted to the Order of the Knights of Santiago, to prove his artistic nobility. According to Ortega y Gasset, "Velázquez's authentic vocation was to be noble". Velázquez had two difficulties, firstly, the requirement for purity of his bloodline, and secondly, that he did not live by a craft. The idea of pure blood was to identify the pure blood of Christians (blue veins) without Hebrew or Moorish descent. The second requirement was to differentiated them from the peasants who worked outdoors. The nobles demonstrated their purity of blood, holding up their arms with their swords to show the bluish veins under their pale skin, unmixed with dark skins. From this custom was coined the term "blue blood", which is still used to differentiate ordinary people from royalty.

Restoration

Restoration of Las Meninas was fraught with difficulties, for the painting had been modified and restored several times during the last 350 years. Deep tears and scratches had been repaired, some areas had been repainted, and at times a layer of thick varnish was considered fashionable. The painting itself is made up of three cloth bands, but the joints move whenever the canvas is moved. And of course there is little or no information on past restorations.

The first 'restoration' of Las Meninas occurred in 1734. The painting was hanging in the Real Alcázar de Madrid when the palacio was damaged by a fire on Christmas Eve. The fire damaged the left and right edges, and these were cut and removed. The high temperature also caused a loss of pigment in some parts, including one cheek of the Infanta. It also altered a little the original colours. Juan García de Miranda (1677-1749) quickly cleaned and restored the painting, and in 1772 it is recorded as hanging in the new Palacio Real de Madrid.

Over time the paint was gradually absorbed into the fabric, and certain 'pentimenti' started to appear. The restorers felt that Velázquez might well have wanted some of these changes to be almost visible in order to convey a sense of life and movement. On the positive side, what the restorers also saw was that the pictorial layer was often still intact, despite the use of a hot iron during the re-lining process. The thick brushstrokes were still there and had not been crushed, and they could still see the way Velázquez would drag an almost dry single point to create a kind of veiling effect. What they also saw was that Velázquez would have worked quickly and with a total lack of hesitation. Once the canvas primed he started to work with a basic pigment and broad brushstrokes, in many cases the areas don't represent figures or the background. Later these areas did not receive much additional pigment, and being barely covered they have a light radiographic contrast. There are no characteristic lines outlining the perspective used. Velázquez placed the figures on the canvas without the need for templates or perspective outline, confirming the hypothesis of a painting created "alla prima".

The use of lead white mixed with other pigments, produces a greater contrast under X-ray examination. Some of the lightest areas are almost pure lead white, meaning that they absorb the X-rays and show up as intense reflections on the photographs. The restorers could see that originally Velázquez was turning to the right with his head towards the canvas. Also it is possible that the lady-in-waiting Marcela de Ulloa may have originally been placed behind Velázquez. Some experts have argued that the shadow might have been for the Infanta María Teresa, who surprisingly was not included in the final painting. In the X-ray they could seen the outlines of the face of the Infanta, the eyes and the loose hair. They could see the mirror and the curtain, but not the reflected portraits of the royal couple. This has led some experts to suggest that the royal couple were added later. Other experts have noted that the fine details suggest that the King was added first, then the Queen. The X-ray photographs also show the 'pentimenti', e.g. the position of a leg or hand changed, and even the Infanta holding the small red-glazed pot.

Perhaps the most important part of the restoration was the removal of old varnish and dirt which had left a uniform amber tone to the entire painting. The overall good condition of the pictorial layer, its perfect adhesion to the support, and the lack of serious damage meant that the old varnish could be lifted. The idea is to use solvents to lift almost all the varnish, just leaving a slight film that protects the pigments.

The article of Manuela Mena Marqués provides an excellent insight into the restoration process, and below we can see just one example taken from the same article.

Las Meninas - a royal portrait

Is this a royal portrait, given that eight people, and the dog, are not royal? Setting aside the fuzzy images in the mirror, the only royal in this painting is the Infanta Margarita. That's why the painting is called Las Meninas, the ladies-in-waiting. But the size of the portrait, 318 cm by 276 cm, would suggest that it was an important painting. In addition the size of the portrait means that the figures are almost life-size (something that can only be seen by standing in front of the original). In fact the figures are ⅔ life-size, but the way the perspective is developed they look almost life-size. A ⅔ life-size was unusual for a royal portrait when the norm would have been life-size, or 'natural'. The reduction in size was probably conditioned by the need to squeeze in all the characters. And Leonardo no less, had written that with 'perspective' every object must be smaller than the original as long as the distance between the reflecting surface and eye is less than that between the surface and the objects. This meant that if people were life-size they would appear to be on the surface of the canvas, whereas being smaller than life-size they appear behind the canvas surface, creating a sense of depth. This argumentation is developed in the article of Luis Ramón-Laca, who supports the idea that Velázquez used mirrors to create Las Meninas.

Also we should remember that in the 17th C 'familia' included parents and children, and servants and slaves. So perhaps this is a family portrait, and thus a royal portrait. Some experts might argue that the 'familia' of Felipe IV included all subjects of the king, including those in the New World. It is said that a Hapsburg ruled over a family, not a state. We do not know why this painting was commissioned, and there are no documents from the period available, not even a payment to Velázquez. In fact the painting was only catalogued in the royal collection in 1666 as 'La Familia de Felipe IV'. Later is was called 'The Empress with her Ladies and a Dwarf', then 'Infanta María Teresa' (by mistake they thought at the time it was a portrait of the daughter of Felipe IV from his first marriage with Isabel de Borbón). Finally in 1843 the Prado decided to call it Les Meninas.

Some see the Infanta Margarita, surrounded by courtiers, as a symbol of royal power and absolute rule. Others see someone who is lonely, burdened by authority and responsibilities. Astute observers see Don José Nieto as an important figure, but whose devotion to the royal couple was in doubt. Is his place in the doorway, not in but not out, a little pointer to his hidden intentions.

Some experts have noted that Velázquez was the only painter to be allowed to portrait the King. Yet at the time Las Meninas was painted (1656), his previous portrait of the King dated from 1644. The reality was that Felipe IV did not like Velázquez showing how old he was, particularly as compared with the Queen, 30 years younger. One suggestion is that Las Meninas was simply a way to paint the King's portrait while stopping short of actually making a portrait. Experts are divided, but some suggest that initially the mirror only showed the King, and that the Queen was added later. This idea looks shaky since Las Meninas contains a number of members of the Queen's retinue.

Almost immediately Las Meninas was recognised as being different. It was ambitious by its size, by the number of different characters, by the status of each, by the variety of actions they represented, by the iconographic references, by the sophisticated perspectival system used, and by the complex narrative intended. And above all by the move away from the Albertian 'window' concept toward the creation of a visual puzzle with both the artist and the viewer integrated into the scene. Some experts have called it a 'labyrinth of symbols'.

The political context

The article of Byron Hamann highlighted two questions. Firstly, what role did the Infanta Margarita really have in this royal portrait? And was Velázquez in some way trying to show us the emptiness of the Spanish imperial splendour?

One study, for example, focused on the royal status of the Infanta, thus endowing the entire painting with a political content. At the time the Infanta was the only child of Felipe IV and Mariana of Austria (1634-1696). Baltasar Carlos, the son from the King's first marriage, had died in 1646 at the age of 10. The portrait Las Meninas is staged in one of his old rooms (he was the 'Principe' in the Cuarto del Príncipe). So the dynastic succession rested on the shoulders of the Infanta, presented in a room that had already seen the death of the 'first in line'.

In 1656 they are not to know that the Infanta would die in 1673, at the age of 22. Nor do they know that only a year later the Queen would give birth to Felipe Próspero, who would die three years later. And finally, in 1656, I don't believe that even Felipe IV was expecting to father another son, Carlos II (1661-1700).

Despite the Spanish colonial empire, the country was almost continuously in financial difficulties, and had declared bankruptcies in 1647 and 1653. Byron Hamann points out that during the period 1654 to 1658 (Las Meninas was painted in 1656) Felipe IV needed an annual income of 27 million ducats, but his 'income' was only 6 million ducats. Hamann even quotes a letter noting "there have been many days the household of the King and Queen lack everything, including bread", and that private individuals "help with this difficulty". Velázquez, as the royal chamberlain, was also responsible for ordering firewood, etc. and he noted "there is not a single 'real' to pay for wood for the chimneys of His Majesty's quarters". When Velázquez died the Crown still owed him seventeen years of salary payments.

We have to remember that Felipe IV became King in 1621 at the age of 16. The first thing he did was place his utmost confidence in the Count-Duke of Olivares, Gaspar de Guzmán (1587-1645). The Count-Duke was prime minister from 1621 to 1643 and drove Spain into total disorder and bankruptcy. He committed Spain to recapturing Holland which led to the renewal of the Eighty Years' War (1568-1648), while Spain was already embodied in the Thirty Years War (1618-1648). Increasing wartime taxation led to revolts in Catalonia and in Portugal, which finally led to his downfall. Ultimately Spain lost the Dutch provinces, most likely because it simply could no longer afford the expenses of war.

Perhaps the portrait Las Meninas was designed to show a courtly audience, dynastic stability and imperial wealth.

Economic difficulties and unsuccessful wars

What you have read above is more than what is usually presented alongside the description of Las Meninas. Yet is it all the story? Felipe IV lost his first wife, Isabel de Borbón, in 1644, and then in 1646 he lost his first son Baltasar Carlos de Austria (the same year he lost his sister María Ana). In 1647 he would marry, for the second time, to Mariana de Austria, who was 30 year his younger. From this union they would have five children, but only 2 would survive to adulthood, Margarita Teresa de Austria (who at five years old was the subject of Las Meninas), and the future King of Spain Carlos II (1661-1700). In 1640 Felipe IV had to deal with a revolt in Catalonia, and a revolution in Portugal and the start of the Guerra de Restauración Portuguesa (1640-1668). Not to mention the Conspiración del Duque de Medina Sidonia in 1641 and the Conspiración del Duque de Híjar in 1648. And not forgetting the exile in 1643 of the Conde-Duque de Olivares, prime minister of Spain for 22 years. At the same Spain was involved in the Thirty Years' War (1618-1648) and the Franco-Spanish War (1635-1659). Less well known was the plague that hit Spain in the years 1647-1652, and which killed anything between a quarter and half of the population of Sevilla, and claimed 600,000 to 700,000 lives throughout the Spanish mainland.

By 1656, and the birth of Las Meninas, Felipe IV considered himself old (he was 51 years old), and he had not yet provided a male succession. Yet some have noted that Spain was going through a 'Golden Age' with great palaces being built, and great artists and poets flourishing, e.g. El Greco, Velázquez, Zurbarán, Murillo, and Cervantes. The courtesan culture that constantly revolved around a monarch, reached its peak with Felipe IV. And the portraits of the royal family painted by Velázquez were a kind of 'propaganda' supporting the absolute power of the King. It is for this reason that Las Meninas stands out, in that it was an 'intimate' view only to be seen by a privileged few. The mistake, if we can call it that, was that the Spanish Court was totally isolated from the reality of everyday life. Correspondents of the period were far more realistic, noting Spain's economic difficulties and the constant pressure of unsuccessful wars. The total 'self-absorption' went as far as an extreme inbreeding, with Felipe IV and his second wife Mariana being uncle and niece (remembering that she was only 14 years old when she married the 44 year old Felipe IV). This inbreeding meant that there is a constant confusion between the portraits of the royal household, e.g. is it a portrait of Mariana, María Teresa, or Margarita? Dynastic systems often look to reinforce political alliances, and Felipe IV married again only to ensure a "casa liena de niños" (a house full of children) even if he considered his new wife "well grown for her age, but very young". Felipe IV was a realist and he wrote "although the bride is now beginning to bear fruit, the groom is already in the last stages of this job". However, by 1652 Felipe IV had become very attached to his second wife, and increasingly he valued the family life she had given him. But until the birth of Carlos II in 1661 Felipe IV had been constantly worried about the lack of a male to guarantee the succession. One writer of the time noted of Felipe IV "in this of bastards has a very good hand, and in the legitimate ones a very short happiness".

Elite artistic culture

Did Velázquez, by depicting himself painting in the presence of the Spanish monarchs, mean to defend the nobility of painting as an art? To turn away from the idea that painters were just craftsmen.

Byron Hamann noted that during his period in Madrid Velázquez was trying to become a member of the Order of Santiago. However there was a problem. He was excluded from membership because he "practiced a manual or base occupation", such as making a living as a silversmith or painter. With the help of a letter from the Pope, Velázquez would finally become a member a few months before his death. So many experts have seen Las Meninas as a personal statement about the nobility of his art. Hamann points out that Velázquez often appropriated references to other artists, but in this painting he appears to be making numerous references to his own past works as a painter in Seville.

Velázquez's desire to become a member of a prestigious chivalric order might seem ridiculous. But at the time nobility conferred power and influence, and all the chief officers of the Court were nobles. The King finally set in motion the nomination process in 1658, and more than 1200 pages still exist and show an immensely laborious process. They had to establish the purity of Velázquez's bloodline, and determine the exact nature of his work. Painting was seen as a manual activity, and painters would 'soil their hands' by actually selling their work. Making money by manual work was anathema to Spanish ideals of aristocratic behaviour. Velázquez had to prove that he made no money from painting. The 'selection committee' asked 10 questions of a variety of witnesses. Question 6 asked if anyone knew "that the said Diego de Silva Velázquez, his father and grandparents on both sides, has been or are now either merchants, or money hangers, or have held any low, or mechanical office, and they should say…". Clearly in Seville Velázquez had lived by selling paintings (a mechanical activity), and in Madrid he was paid as pintor de cámara. The story goes that with the written support from the Pope Velázquez made his request to the Order of Santiago, but it would still take another eight years for him to obtain a royal nomination. Even then they rejected his request because of the basic contradictions between the painter's 'God-given talent' and the 'man-made hierarchy of Court'. I've no idea what that really means, but Velázquez brought a legal action against the decision. The trial involved 148 witnesses, and the topic focussed on his nobility, and all the witnesses affirmed that he never worked for money because as an aristocrat he did not need to. This was manifestly untrue, but a new letter from the Pope and the ennoblement by the King finally removed all the obstacles. He was admitted to the Order on 28 November 1659, and he died on 6 August 1660.

A secondary source also suggested that, based upon the list of books that were owned by Velázquez, he was trying to show that for the 'ancients' painting was an activity that was carried out by people of high-rank. Thus supporting his aspirations to achieve a degree of nobility.

Velázquez is not dressed as a painter, nor as a courtier. We can see on his breast the cross of the Order of Santiago. Palomino wrote that it "was painted after his death at the order of His Majesty. Some say that his Majesty himself painted it, for when Velázquez painted this picture he had not yet been granted this honour by the King".

Others have suggested that the key suspended from Velázquez's waist is the one that opened all the doors in the palace, including the King's private apartments. He was both chief palace chamberlain (aposentador mayor de palacio) and assistant in the privy chamber (ayuda de cámara). The key was a symbol of Velázquez's high office and the special relationship he held with the King. You cannot really see the key in the photographs, but in real life it easy to see, if you look for it.

The job of aposentador was a considerable honour, but with it came considerable responsibilities. Velázquez had to oversee the cleaning and maintenance of the King's quarters. He had to stage many of the important rituals of Court life.

Including José Nieto, the aposentador of the Queen, in Las Meninas was an important sign of respect. Also his role was to be in attendance upon the Queen and to open and close doors for her. So some experts see Nieto in the Las Meninas as simply 'doing his job', and waiting to lead the Queen out of the workshop. Everything in Las Meninas has been examined and analysed over and over again. Some art historians look at the painting and note that the horizontal centre is occupied by the Infanta, and the vertical centre by the mirror. The Infanta is flanked by the meninas, and the mirror is surrounded by a 'U' of figures. Velázquez and Nieto, the two chamberlains, bracket the mirror and thus flank the royal couple. Because experts enjoy reading signs based upon the most fragile facts, they concluded that the aposentador of the King was a superior post to that of the Queen, and for this reason Velázquez's head is slightly higher than Nieto's head!

There are also important references to art-history, expressed in part through the presence of the painter himself and in part through the paintings hanging on the rear wall. It is extremely rare for 17th C paintings to depict a real place, yet here we see a real room in the palacio, with its real-life decoration. According to an inventory made in 1686 the room contained 40 paintings, almost all by another Court painter, Juan Bautista Martínez del Mazo (ca. 1612-1667), and most being copies after compositions by Rubens. It is almost certain that Velázquez as 'aposentador mayor de palacio' would have been responsible for the decoration of the room, including the hanging of the paintings.

Las Meninas is presented in the room where numerous paintings are already hanging. Velázquez has chosen mythological themes in which the Gods punish the arrogance of the artisans. We can just about see the two larger paintings on the back wall.

Some experts claim that the paintings are 'Pallas and Arachne' by Rubens (left) and a copy of 'Apollo as Victor over Pan' by Jacob Jordaens (right). Other experts claim that they are 'Prometheus Stealing Fire' by Rubens, and 'Vulcan Forging the Thunderbolts of Jupiter' also by Rubens. Both options support the idea of mythological practitioners of the manual arts, but I prefer the first option based purely on the size and shape of the frames.

One reference highlighted the strong relationship between the King and Velázquez, "confianzas más que de un Rey a un vasallo, tratando con él negocios muy arduos", which might translate as "the King treated him with greater familiarity and trust than is normal to a vassel, discussing with him very difficult matters".

Stepping back from Velázquez for a moment, we must understand that everything depended upon painters being considered an integral part of the 'liberal arts', something that had often been denied. Even today painting is not explicitly mentioned in the Wikipedia article on the topic. In the case of Velázquez, the Order of Santiago excluded those of impure blood and those who did manual work, including painting. However, we know that some of the most influential intellectuals and courtiers at that time, often members of the Order, included painting as a liberal art, along with mathematics, music, arithmetic, topography, poetry, moral philosophy, etc. Some even raised painting and sculpture to being 'imitations of the works of God'.

The importance of portraits

The key to lifting painting into the liberal arts was certainly linked to the arrival of a new Queen, the Infanta María Teresa, and the birth of later children. Portraits became an essential element in the politics of the state. The Spanish royal house needed to put on display and guarantee the future of the monarchy. They needed to send portraits to foreign royal houses, and they needed to show servants, subjects and allies alike that the Spanish monarchy was ready for the future. Finally we must not forget that having a royal portrait was a sign of great importance, since it showed that you were both loyal and held a favourable relationship with the King. For example, Felipe IV made himself known to his second wife with some jewellery and a portrait. Cristina of Sweden (1626-1689) tried to approach Felipe IV by send him a painting by Dürer and a royal portrait. In 1656 when France and Spain finally talked about peace and a possible marriage alliance, they exchanged portraits (and portraits of María Teresa had already been sent to Brussels and Vienna). It is said that already in 1653 France, whilst still at war with Spain, had secretly asked for her portrait.

Powerful families did not hesitate to show off their collection of royal portraits. One family had a collection of about 300 paintings, many representing saints, etc., as well as members of the royal family. Those who took on great responsibilities of State wanted (needed) a royal portrait to show both their relationship to and loyalty to the King. For example, when the Secretary of State for Castile died in 1674 he owned just over 100 paintings, 16 of which were royal portraits, including 4 full-length portraits of the King, Mariana, Marías Teresa and Margarita.

Yet Velázquez retained a virtual monopoly on royal portraits. For example Ferdinand III (1608-1657) specifically asked to have portraits of his daughter Mariana and his granddaughter Margarita (sent in 1652 and 1654 respectively). The church was also a continuous demander for portraits of the royal family. Pope Innocent X (1547-1655) returned from Madrid in 1630 with five royal portraits, and later he would pay 1,200 reals to add another four (Velázquez painted his portrait ca. 1650).

Felipe IV even accused Velázquez of "cheating me a thousand times" before finally delivering on one or other portrait. Felipe IV was even the more insistent because he did not want Velázquez to start producing portraits showing how old he was. Velázquez's absence during his second visit to Italy (end-1648 to mid-1651) was not appreciated by Felipe IV. And to 'add insult to injury' Velázquez was painting portraits in 1650 in the Papal Court in Rome. Velázquez was so successful in Rome that copies and paintings inspired by, or 'in the style of', still can raise attribution problems.

The way around the excessive demand for portraits was to have a workshop with a team of assistants, and to differentiate between 'representations' and 'works of art'. The workshop would also produce copies of masterpieces purchased by the King or already in the royal collection. One of his assailants Juan Bautista Martínez del Mazo (1612-1667) was a specialist in copying Rubens and Titian, and upon the death of Velázquez he was nominated royal portraitist and continued to produce portraits. We tend to look at portraits differently now, but at the time they were more than anything else utilitarian objects, much like our collections of photographs today. This is why the portraits of the 1650's all look very similar, e.g. same stance, same background, same colours, and more or less the same expressions (majesty, arrogance, call it what you will).

Courtly painting and the image of the King

Above we looked at the role of the portrait, an object of power and at the same time a utilitarian object much like our photograph collection today.

However, the portrait was just one element in a far larger 'revolution' created with the death of Felipe III (1578-1621) and the arrival on the throne of a 16-year-old boy, Felipe IV (1605-1665). You can imagine that initially in the years 1622-1626 expensive festivities were the norm. Felipe IV first leaned on Baltasar de Zúñiga (1561-1622), who had been his tutor from 2019. He then turned to the Conde-Duque de Olivares (1587-1645), who was prime-minister from 1621 to 1643. In the new government of Felipe IV there was a reformist zeal, with the dismissal of the 'old generation' and new ministers appointed. The 'old generation' were accused of being responsible for the 'decline' of Spain, and old 'favourites' were exiled, imprisoned, or even executed. Laws were enacted to improve the states administration and finances, and ministers were obliged to declare their assets before taking office. Laws were also passed to limit the luxury in clothing, household goods, furniture, etc. This last measure might seem trivial or symbolic, but it affected the way the Court and the monarchy managed their 'image'. Through the period from (say) 1618 to 1623 everything changed. The government, the appearance of courtiers, and even the city of Madrid, which in 1619 saw the completion of Plaza Mayor.

There is nothing better to understand the ideal of reform, austerity and public commitment with which the reign of Felipe IV was inaugurated than to see how successive norms impacted the image of courtiers. Firstly the King looked to replace calzas (leggings, stockings, tights) by the so-called gregüescos (kind of braided breeches or shorts, quilted or puffed out). These quilted breeches appear to us as quite elaborate, but at the time they were seen as more modest than a 'manly leg' in tights. They also hid more comfortably the new trend to carry a cloth or leather bag over the groin (like a 'fly'). The new style of gregüescos were longer, narrower and in general much more discreet, according to the new ideals. The unofficial beginning of this new fashion took place on September 25, 1622, on the occasion of a wedding, where we are told, "it was the first time that all the gentlemen got short pants and undergarments".

Reforms continued, all guided by the principles of austerity and rationalisation. These reforms were enacted just before Velázquez arrived at the court. Merchants to the Court were reduced by ⅓ and they could only stay at the court for 30 days per year. Nobles were forbidden to stay in Madrid unless it was absolutely necessary, and they could only be accompanied by up to 18 servants. The use of gold and silver were limited, "the use of gold and silver, in cloth and garrison, inside and outside the home, and in everything and any clothing genre (...) except for the cult divine, war suits, and cavalry dressings". The most important provision was number 14, "we order that all and any persons of any state, quality or condition whatsoever, must wear flat vallanas, and without invention, tips, cut, frayed, or another sort of garniture, neither garnished with rubber, powders, blue, or of any other colour, nor with iron; but we allow them to carry starch". It meant the demise of the complicated and expensive lechuguilla (necks ruff), and their replacement with a much simpler and cheaper type of collar.

Part of the problem was that what had once been considered luxury items had over time become obligations. A voluntary or optional expenditure had become an obligatory expenditure on both master and servants.

What was even more impressive was that changes were introduced almost immediately, and that the royal family showed the example. Above we see Felipe IV in 1622 and 1624. The change in collar ruffs came in, and on the same day the King was seen having made the change. Six days later the whole court had changed. I suppose Velázquez was part of that renewal and move to a more austere image. Above on the left we have a portrait by Rodrigo Villandrando (1588-1622) and on the right the first portrait of the monarch by Velázquez.

As you might expect there were massive inconsistencies. Felipe IV stopped the Madrid City Council sponsoring public games, but accepted the enormous expense associated with religious festivals. For example, Charles I of England (1600-1649) visited Madrid in 1623 (see the so-called 'Spanish Match') to request the hand of the Infanta María. He stayed in Madrid six months, and the constant festivities (banquets, chivalric games, processions, etc.) made it one of the most costly periods ever seen in the capital. Naturally the nobles had to keep up with the King, giving expensive gifts to Charles I and hosting tournaments and banquets. In addition religious precessions were made all the more splendid in order to affirm the cities Catholic faith before the heretic Anglican. In 1626 Cardinal Francesco Barberini (1597-1679) was sent to Madrid by the Pope. He was received with the same splendour as reserved for Charles I. He documented his visit, so we know that it consisted of a constant stream of visits to aristocratic houses, endless entertainment and an inexhaustible series of exchanges of gifts. Probably there is no chronicle that document so faithfully the luxury that existed in the Court at the beginning of the reign of Felipe IV. Everything could be given and received: jewels, works of art, perfumes, reliquaries, objects of devotion, novo-hispano vases and oriental porcelains, clocks and scientific instruments, plants and natural history rarities, etc.

During those years, the new court of Felipe IV was offering the first symptoms of a phenomenon that with the passage of time would become one of its hallmarks of historical identity: the love of painting. Perhaps the most impressive were the set of six mythological pictures that Titian painted for Philip II, and that his son hid due to its erotic content. For many years, nobody could see them. They were scattered in the 18th C, but they included Danaë (c.1553, Apsley House, London), Venus and Adonis (1554, Museo del Prado), Perseus and Andromeda (c. 1554-56, Wallace Collection, London), Diana and Actaeon (1556-59, National Gallery, London), Diana and Callisto (c.1556-59, National Gallery, London/National Galleries of Scotland, Edinburgh), and The Rape of Europa (1559-62, Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston). One of the first measures taken by Felipe IV was to create a collection context for them. In 1623, the same year that Velázquez arrived in Madrid, those paintings were placed in a group of rooms located in the northern part of the palace. The rooms had been used by the royal family during the hot summer of Madrid, thus avoiding a move to El Escorial. These rooms, intended for the privacy of the King, were decorated with a mixture of family portraits and mythological paintings (mostly by Titian). For its themes and the painters represented, it can be considered the first model from which the very personal collector's taste of Philip IV and his court would develope. The operation as a whole also announced a taste for painting and a hedonism that would differentiate Felipe IV's reign from that of his father. Soon there would be occasions to expand the king's collection with great works. The execution of Rodrigo Calderón (1576-1621) not only served to remove a political opponent from the field, but the King was able to buy the splendid Adoration of the Magi by Rubens (now in the Museo del Prado) in the auction. After the visit of Rubens to Madrid in 1628-1629, he would become one of the poles around which the royal collection would be organised. In that context the appearance of Velázquez in 1623 proved providential for both the King and the painter.

Initially the attitude of the King was multiple, as was the attitude of the court. Depending on the context, it could be austere or splendid. In most of the occasions in which Philip IV is described, attention was drawn to the richness of his clothes and not to the austere design. The allusions to the king's indulgent luxury were multiple and constant. We find mention of "a brown dress set with gold embroideries"; "embroidered with gold and all the buttons of diamonds", or "in black, gold and priceless diamond jewels".

However, in 1623 a decisive event occurred that would change the history of the Spanish court portrait. Namely the arrival of Velázquez at the Court as painter of Felipe IV, a task in which he was employed until his death in 1660. With his first paintings of the monarch the Court was exposed for the first time to the concept of a 'real image'. They began to understand that a portrait, in the hands of an intelligent artist, could both support the generic ideals of the monarchy and be part of a political strategy. Until around 1620 sacred images and royal portraits followed more or less the same rules. Start with the images of Christ, and extrapolate to those of the Kings, "it is also (necessary) that it has perfection and property, because if the image of Christ our Lord being painted with majesty and beauty, will cause us reverence and love, and if it were painted with ugliness and indecency, it will do contrary effect".

Naturally this has a specific context, with artists being deeply interested in controlling their professional activities through the standardisation of their art, and delivering what the church and state expected. Not everyone held that opinion. Felipe II was known to not care about poor quality portraits circulating, and the 'cronista' of Felipe IV wrote "There is no portrait so bad that it does not say something good". However Felipe IV was very much aware of the need to take care of his image from the point of view of its content and quality, and in some occasions that awareness became explicit and was translated into very concrete measures.